Birds sing longer in areas with light pollution

Light pollution is causing birds to sing more, prolonging their vocalisations by an average of 50 minutes, according to a study published in Science. The study, which analyses more than 580 species of diurnal birds, shows that those most exposed to light, either because they have large eyes or open nests, are the most affected by this phenomenon. The authors analysed more than 60 million vocalisations from the BirdWeather citizen science project. ‘The machine learning algorithm allows us to analyse audio recordings 24 hours a day, seven days a week, which would otherwise take a lifetime to listen to,’ says Breant Pease, one of the authors.

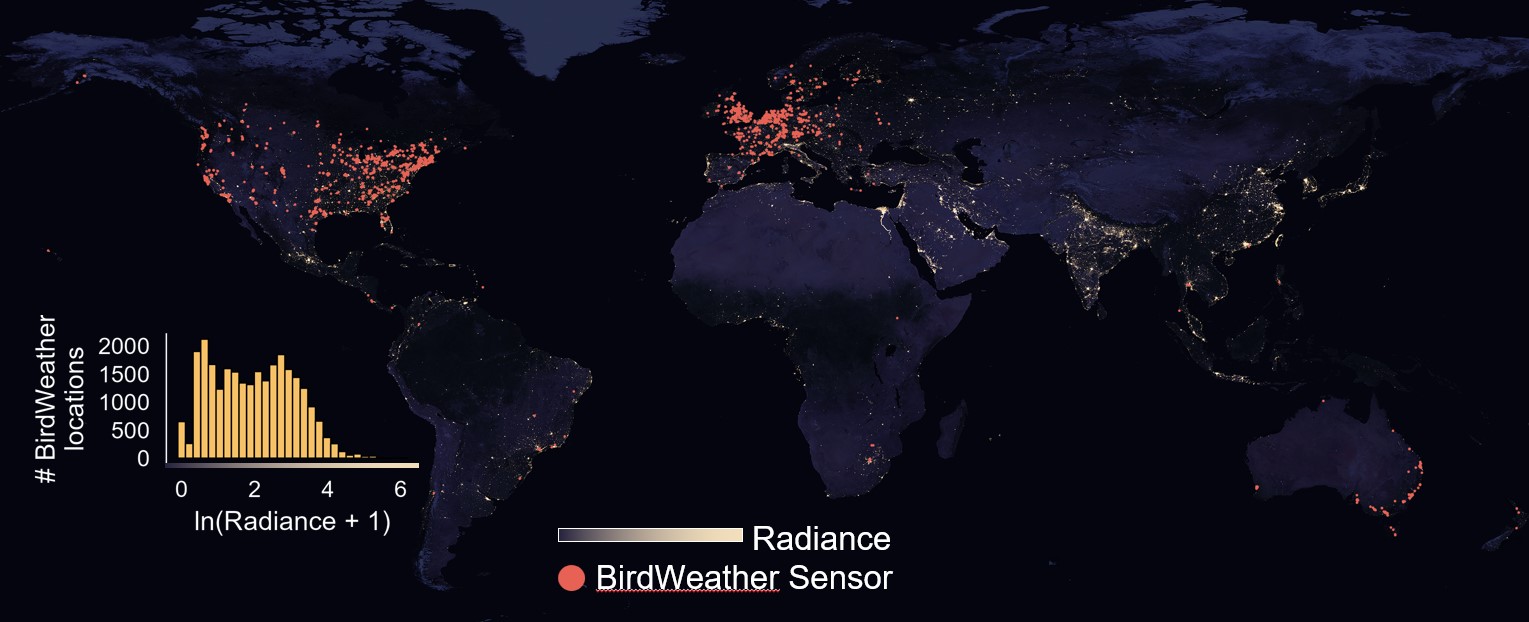

A map of global BirdWeather locations. Credit: Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Graciela Gómez - contaminación lumínica aves EN

Graciela Gómez Nicola

Full Professor of the Department of Biodiversity, Ecology and Evolution at the Complutense University of Madrid

Compared to other types of pollution, such as noise or chemical pollution, light pollution is particularly harmful to animals because it disrupts their biological rhythms. Almost a quarter of the Earth's surface is affected by this type of pollution; however, scientific studies on its effects on wildlife are relatively recent. Pease and Gilbert present a very rigorous study that represents a significant advance in understanding how excess artificial light at night affects the vocal behaviour of birds globally. The use of emerging technologies such as acoustic sensors and machine learning algorithms, combined with the collaboration of volunteers in gathering information, has made it possible to collect an unprecedented volume of data, around 60 million detections of 583 species of diurnal birds in more than 7,800 locations worldwide.

Analysis of this robust database has shown that this type of pollution prolongs bird song by almost an hour on average, especially at night. Furthermore, the effect is more pronounced in species with larger eyes, more open nests or migratory habits, as well as during the breeding season. These are undoubtedly striking and novel findings, but they also leave many questions unanswered, such as what positive, negative or neutral consequences these changes have on the ability of species to survive and reproduce in their respective environments.

Kristal Cain - contaminación lumínica aves EN

Kristal Cain

Associate Professor, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland (New Zealand)

In recent years there has been a tremendous amount of interest and concern about how the amount of light humans are pumping out is affecting the world around us. The problem has been that it is difficult to do the really big studies that are needed to understand which animal are getting affected the most, and why.

"This paper using the bird song data collected by thousands of volunteers and measured when birds start singing in the morning and when they stop for the night. They found that in brighter areas – birds start singing early and keep going later into the night than in dark areas. Importantly, most of the bird song was collected in North America and Europe. We still need to do similar work in the rest of the world to see how widespread these patterns really are. The manu of Aotearoa are quite unique in many ways. Even more importantly, we need to know how this affects the birds’ survival and reproduction.

"Some evidence says too much light stresses birds out and makes them more vulnerable to infection and disease – but the lack of sleep might also mean they have more or healthier babies. Importantly, all this artificial light is not good for us either. So, it’s good for everyone to limit light at night to only when it is necessary. There are lots of little things we can do as individuals and as communities to reduce the amount of light that animals experience at night. For example, closing your curtains can do wonders, make sure the lights are only on when needed, and are no brighter than needed. Communities can put shields on streetlights, so they don’t spill light everywhere, use warmer light colours, and plant trees to contain some of the light. Check out this webpage for information on more steps to take.

Conflict of interest statement: "No conflict - but also have done research on light at night."

Brent S. Pease et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed