Android earthquake early warning system proves effective on smartphones

Between 2021 and 2024, the Android Earthquake Alerts system detected an average of 312 earthquakes per month and sent alerts in 98 countries associated with 60 events of magnitude greater than 4.5, according to a study published in the journal Science. The study also includes comments from users who received the alerts: 85% said they felt tremors, 36% received the alert before noticing them, 28% during the event and 23% after they occurred. In addition, 84% said they would trust the system more next time, according to the research team from Google and the universities of California - Berkeley and Harvard (USA).

Galderic Lastras - alerta terremotos Android

Galderic Lastras

Geologist and professor at the Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Barcelona

The article explains how Google has turned our Android smartphones into instruments that can detect earthquakes using the accelerometer installed in all devices and use these detections to generate alerts that are sent to the smartphones themselves. In a high percentage of cases, [these alerts] arrive before the earthquake itself and can therefore be a tool for reducing potential damage.

In fact, we saw the system in action [on Monday 14 July]. An earthquake struck off the coast of Almería and numerous X users posted screenshots of their smartphones with the warning sent by Google, for example here.

How does the system work? Once an earthquake has been generated – which, let us remember, neither geologists nor anyone else is capable of predicting (i.e., predict the exact day, time and place where it will occur) – seismic waves begin to spread from the hypocentre (or focus of the earthquake) and, on the Earth's surface, we feel and measure them with seismometers as they reach our location. Naturally, places closest to the hypocentre receive the seismic waves before places further away, meaning that the tremor is not felt instantly everywhere, but spreads outwards.

Researchers at Google, the University of California and Harvard have implemented a feature in the Android system since 2021 that means that when our phone is in standby mode, if the accelerometer detects waves similar to seismic waves, it sends a message to Google's servers with the information and the location of the phone. When Google's servers receive this information from multiple phones, they use it as a kind of pedestrian network of seismometers that allows them to locate the source of the earthquake, as well as its magnitude, which is what geologists do with seismometers. This is certainly very interesting and, in a way, it is ‘unintentional’ citizen science, as it is implemented in Android by default.

The second part is also very interesting: once an earthquake has been detected, Google uses this information to send an alert to all phones located in the potentially affected area, similar to how Civil Protection sends alerts with the EsAlert system, which has recently become famous (for not being sent in time during the storm in Valencia or for being sent on Saturday [12 July 2025], in the case of Catalonia, to the entire population). It should be noted that, in this case, the decision to warn the population is not in the hands of Civil Protection, but in the hands of a private company.

As seismic waves travel at high speed (this is not a storm that arrives two days later, but seismic waves that spread in a matter of seconds), the criteria for sending the alert are automatic and therefore do not depend on a decision to send or not to send. Despite this, in some cases, the alert arrives during the earthquake itself or afterwards, when it is no longer useful. However, in a significant number of cases, especially the further away from the earthquake's epicentre, the alert reaches the phone before the seismic waves themselves, giving the recipient a few seconds to protect themselves. It is therefore an Early Warning System (EWS), a kind of ‘seismic wave arrival forecast’. Several countries around the world (Japan, Mexico, Taiwan, South Korea and the Pacific coast states of the United States and Canada, for example) already have an earthquake EWS in which the detectors are seismometers. This system makes it possible to generalise an EWS for the entire population (who have an Android!) in which the detectors are our smartphones. An added advantage may be that the system allows for much faster mapping of the distribution of intensities (damage) of an earthquake, which is critical during emergency management.

It is important to bear in mind, however, that once we receive the information that ‘we are going to feel an earthquake’ and we have the opportunity to protect ourselves in a few seconds, we must be educated on how to act and how to protect ourselves. Countries that already have an established earthquake SAT also devote considerable resources to educating the population to make us less vulnerable to potential damage.

In Spain, there is no earthquake early warning system like the one in Japan, so progress is significant, as long as it goes hand in hand with public education.

What problems could the system have?

- The alerts do not reach all devices (only Android) and do not seem to be linked to a loud sound like EsAlert.

- The emergency manager (Civil Protection) in this case has no role in the decision to issue an alert (for example: who determines the magnitude or expected intensity at which the population is warned?).

- The detectors (our Android phones) are not evenly distributed across the Earth's surface, but rather:

- In two-thirds of the planet, where seas and oceans are located and earthquakes are also generated, we would not have these detectors. It is often under the oceans, in subduction zones, where the largest earthquakes are generated, which will only begin to be detected when they reach land, where there are smartphones, and therefore too late. It is therefore very important to note that this system cannot replace existing systems, for example in Japan, where seismometers are installed on the seabed, allowing detection closer to the source, which can provide a few seconds more reaction time, crucial in larger events.

- Nor are they evenly distributed across the Earth's surface, and therefore the system is less effective in sparsely populated areas, where the low number of detections does not allow for a high-quality alert to be generated.

- Knowing what is going to happen does not prevent us from experiencing it, and therefore the population must be properly educated, and drills should be carried out so that people know how to act correctly.

- At a time when science, and geology in particular, is gradually disappearing from school curricula, there is a growing need for a thorough understanding of how the natural environment works, enabling us to make the right decisions, both personally and as a society.

Alertas terremotos - Elisa EN

Elisa Buforn Peiró

Retired professor of Geophysics and Meterorology in the Department of Earth Physics and Astrophysics at the Complutense University of Madrid.

Maurizio Mattesini

Catedrático de Geofísica

Earthquake Early Warning Systems (EEWS) are designed to generate alerts when a destructive earthquake occurs. They make use of the time interval between the detection of the first few seconds of seismic wave arrivals at a station near the epicentre and the arrival of the more destructive waves at a more distant location, which allows for damage prevention and mitigation. An EEWS can locate an earthquake and calculate its size—either moment magnitude (Mw) or local magnitude (ML)—using only the beginning of the seismogram. This concept should not be confused with that of an Earthquake Alert, where information about the earthquake’s location and magnitude is sent after it has occurred. On 14 July 2025, after a magnitude 5.3 earthquake occurred southeast of Cabo de Gata (Spain), an Earthquake Alert was issued.

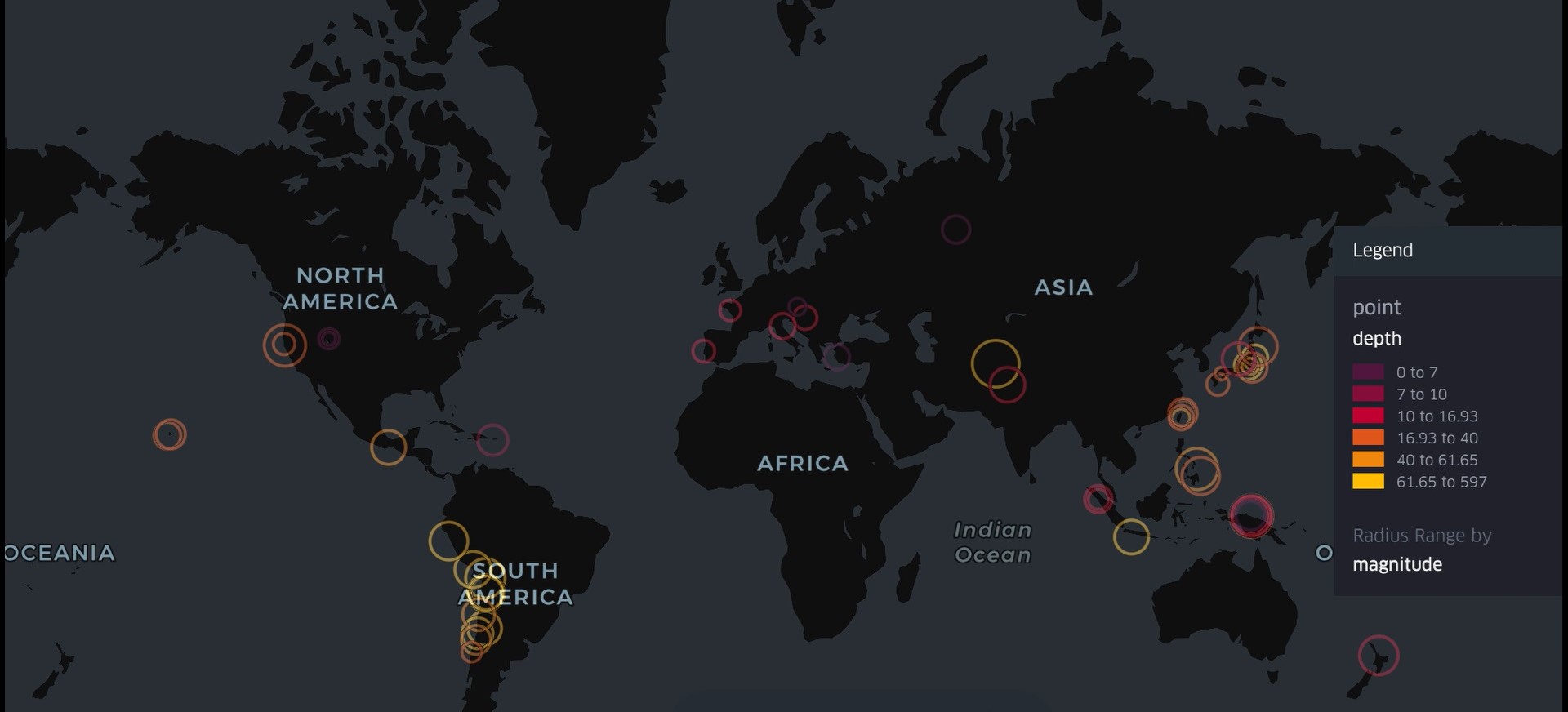

The article by Allen et al. (2025) presents a new tool for Earthquake Early Warning Systems, consisting of the global use of Android smart phones (Android Earthquake Alert, AEA) to detect earthquakes. Therefore, this new EEWS system provides coverage in areas lacking seismic infrastructure and reaches 2.5 billion people—an unprecedented scale. Traditionally, EEWS rely on regional seismic networks to generate alerts. The denser the network, the faster and more accurately the earthquake’s location and magnitude (Mw or ML) can be determined. When this magnitude exceeds a certain threshold—typically between 4.5 and 5.0—an alert is issued. Thus, delays in calculating the magnitude also delay alerts to users. Increasing the density of a seismic network entails significant financial cost and is not always feasible. The innovation of the AEA lies in the fact that smart phones are equipped with accelerometers that record ground acceleration during an earthquake, thereby increasing the availability of seismic instrumentation.

The authors have long been working on this subject, in regions such as New Zealand, Greece (2021), Turkey, and the Philippines (2022). Allen is a pioneer in EEWS development, having created the ShakeAlert system for early earthquake warnings in California. The first EEWS were installed in 1991 in Mexico and in 2007 in Japan, followed later by Taiwan, South Korea, and the United States. It is estimated that currently 250 million people have access to an EEWS. By including AEAs, this coverage expands to 2.5 billion people. Alerts from EEWS and AEAs are similar in their magnitude estimations and margins of error.

One of the limitations of EEWS—and, by extension, AEAs—are larger earthquakes, with magnitudes of 7.5 and above. In many of these cases, the rupture is complex and consists of multiple events, making it difficult to accurately estimate the magnitude and issue timely alerts. This was the case with the 2023 earthquakes in Turkey (magnitudes 7.8 and 7.5). To address this challenge, the authors developed a new algorithm capable of estimating a magnitude of 7.4 just 24 seconds after the earthquake began. Other limitations of the system include accuracy, which depends on the density of available smart phones and the level of ambient noise. Delays in magnitude estimation and false positives—caused, for example, by storms or massive vibrations—can also occur, although these have been progressively reduced through algorithmic improvements.

The authors emphasize that, for alerts to be truly effective, it is essential for the public to be educated in advance on how to act during an earthquake and to know basic self-protection measures. Among the main obstacles to implementing this system are institutional acceptance, integration with national alert systems, potential privacy concerns, and the need for educational campaigns to ensure an appropriate response from the public.

In Spain, in 2010, the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), together with the Royal Institute and Observatory of the Navy and the Geological Institute of Catalonia, conducted studies on the feasibility of an earthquake early warning system in the southern part of the country. In 2015, the first operational EEWS—called PRESTo—was installed in the Department of Earth Physics and Astrophysics at the UCM Faculty of Physical Sciences, in collaboration with the University of Naples Federico II. More recently, in 2024, the same department launched Quake-Up, an updated version of that system. Additionally, just a few days ago, the Community of Madrid awarded a predoctoral contract to Prof. Mattesini as part of the 2024 call for research training grants. This contract will fund a doctoral thesis focused on improving the efficiency of EEWS in Spain.

Currently, Spain has two EEWS systems operating at the research level. However, as previously mentioned, it will be up to society itself to demand their effective implementation and widespread use.

Richard M. Allen et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed