The “body map” integrated into the brain does not change even if a limb is amputated, despite previous belief to the contrary

Various studies claimed that the loss of a limb caused a reorganisation of the “body map” integrated in the brain: neighbouring regions invaded and reused the brain area that previously represented the amputated limb. But a new study refutes this theory. Cortical representation remains stable even when the body suffers the loss of a limb. The team, which published its study in Nature Neuroscience, analysed three people who were about to undergo amputation of one of their hands, studying for the first time the maps of the hand and face before and after amputation, with follow-up for up to five years. Even without the hand, the corresponding brain region was activated in an almost identical way.

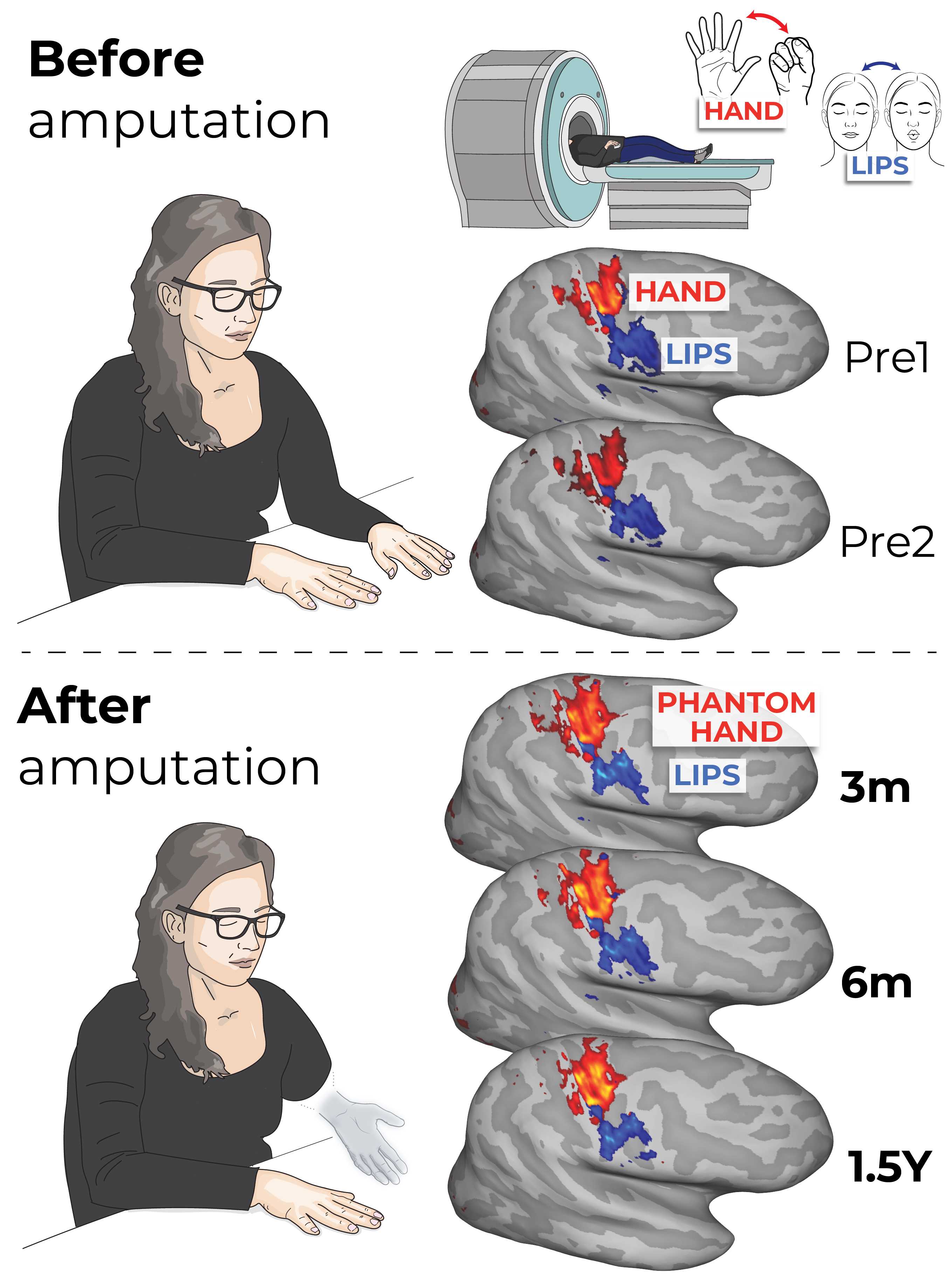

Brain activity maps for the hand (shown in red) and lips (blue) before the amputation (Pre1 and Pre2) and after amputation (3, 6 and 18 months post-amputation). Authors: Tamar Makin / Hunter Schone.

Juan de los Reyes - mapa cerebro amputados

Juan de los Reyes Aguilar

Head of the Experimental Neurophysiology Group at the Research Unit of the Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos, member of the Castilla-La Mancha Health Service (SESCAM), the Castilla-La Mancha Health Research Institute (IDISCAM) and the Spanish Society of Neuroscience (SENC)

The work follows Dr T. Makin's main line of research into the effects of amputation on sensory representation in the cerebral cortex. What is original in this case is that she manages to study how different parts of the body, lips and hands, are represented in the cerebral cortex of people before they undergo amputation. These individuals subsequently underwent surgery to amputate most of their arm (due to a pre-existing condition requiring surgery), which allowed the study to be carried out to determine whether or not there were changes in the cortical representation of the amputated upper limb. In addition, she compared the representations of these three people before and after amputation with those of people who had not undergone amputation, in order to identify similarities or differences.

Dr Makin's work is highly structured from a methodological point of view, and the first result was to confirm that in a natural situation (before amputation), the three people showed the same cortical representation as people who had not undergone amputation, i.e. they started from the same anatomical and physiological basis. She then studied the temporal evolution of the possible changes that amputation should cause in the cortical representation of the three people studied. As explained in the introduction to the article, scientific literature has described that after amputation and spinal cord injury, most people experience a phenomenon of “cortical reorganisation”, which consists of the region of the somatosensory cortex that no longer receives sensory information from the part of the body that has been amputated begins to activate abnormally in response to stimulation of other nearby parts of the body, such as the face, which is close to the arm. Therefore, what has been documented in other studies of amputees or people with spinal cord injury is that the cortical region that is activated when healthy body parts are stimulated expands. However, the main finding of this article is that no changes in the cortical map are observed after amputation and that cortical representation is maintained in people who have been amputated. These results are consistent with those reported by the same research group in previous articles, which compared the cortical representations of people who had been amputated for years with those of people without amputation. Therefore, they demonstrate that the phenomenon of cortical reorganisation is not evident or does not occur in people with amputations, contrary to what has been previously described.

The authors propose that this finding may be important when performing interventions to help people with amputations, such as implanting a bionic prosthesis that allows not only movements directed from the brain but also the proper reception of sensory signals from the prosthesis. Without an altered cortical map, intervention and recovery of functions in people will be easier.

In the context of cortical reorganisation related to a loss of sensory input, there are two models: amputation and spinal cord injury. The first, amputation, does not involve the loss of peripheral neurons where sensory information originates. In this way, the cortex continues to receive information from the periphery to its corresponding sites in the cerebral cortex, therefore, cortical reorganisation is less likely as sensory inputs are maintained. In fact, the article states that during amputation surgery, the nerves that reached the amputated regions were inserted into other muscles of the arm that were spared from surgery. Therefore, sensory inputs are not largely lost and the body map in the cerebral cortex can be maintained. In the second case, spinal cord injury, the damage completely prevents sensory information from reaching the cerebral cortex, and cortical reorganisation, understood as the expansion of activity from the healthy cortical region to the region suffering from the absence of sensory inputs, is more likely to occur.

However, there are data that are not discussed in the study and that could indicate alterations at the cortical level related to neuronal plasticity and/or cortical reorganisation. Thus, the authors conduct a detailed study and follow-up of the type of pain felt by the three individuals before and after amputation surgery. One of the three people reported a reduction in the intensity and frequency of pain after amputation; this may be due to the elimination of the problem in the arm that led to the amputation. However, the other two people report that the pain remains the same or increases in intensity and frequency and, above all, the type of pain perceived changes (from a burning sensation to cold pricks and itching; see supplementary figure 1). These changes indicate an alteration either in peripheral activity (because, as described, the nerves connect to other regions of the arm that produce other input activity) or in the excitability of the cerebral cortex, which alters the perception of signals without affecting touch and proprioception but altering pain.

Given the data on perceived pain shown in the article, it could be argued that the concept of cortical reorganisation after amputation or spinal cord injury is somewhat more complex than is currently described in the literature, which reduces it to an expansion of the activated cortical area, and could focus on alterations in sensory perception. From this point of view, I believe that this work (like the previous ones by the same authors) can contribute to deciphering the complexity of the phenomenon of cortical reorganisation and even redefine it.

Hunter R. Schone et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People