Shown a way in which RNA and amino acids might have begun to relate at the origin of life

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. These are known as the building blocks of life, but they cannot replicate themselves. To do so, they need the instructions provided by RNA. How this relationship began is still a mystery. Now, a British team has shown how it could have started from relatively simple conditions. According to the researchers, who published their findings in the journal Nature, ‘understanding the origin of protein synthesis is fundamental to understanding where life comes from.’

César Menor - ARN vida EN

César Menor Salván

Astrobiologist and lecturer of Biochemistry at the University of Alcalá

This is a chemically elegant, solid, carefully crafted piece of work, as is usual for Powner's group. It shows how good funding can lead to good work.

The first thing to say is that this work does not ‘solve’ the problem of the origin of life at all. Nor does it solve the problem of the origin of the ribosome or the origin of biological protein synthesis.

Rather, it raises more questions. The work shows us a chemical, not biological, route for connecting amino acids to RNA, the key molecule of life. This connection is essential in life as we know it, as it is what initiates protein biosynthesis in cellular ribosomes. In the work, it achieves this in a simple way, without the need for complex enzymatic machinery, using the chemistry of thiols and thioesters, sulphur derivatives of amino acids.

This could apparently solve the biochemical paradox in which proteins and RNA are needed to obtain the peptidyl-RNAs that give rise to new proteins, raising the question of how this cycle began, similar to the classic chicken-and-egg paradox.

The main limitation is its geochemical and prebiotic implausibility. Despite attempts to connect the binding of RNA to amino acids with plausible precursors—such as aminonitriles—and mild environmental conditions, the process is complex, requiring carefully controlled conditions and the precise concurrence of certain reagents at concentrations that are unlikely in a prebiotic environment. Therefore, despite its elegance, this pathway is, in my opinion, unlikely under natural conditions.

Furthermore, the work is based on a well-defined theoretical framework: that complex RNA had a direct prebiotic origin and that RNA-driven peptide synthesis could have preceded the evolution of the larger ribosomal subunit. This is currently highly debated.

Regardless of the theoretical framework on the origin of life, the result is a proof of concept that shows us that complex and precise enzymatic and structural control is not necessary to form an aminoacyl-RNA, as it is easily formed in the same position as its biological equivalent, with an activated amino acid in the form of a thioester and a double-stranded RNA. This suggests that, once the basic structures and conditions are established, the peptide synthesis cycle could easily start.

Other strategies have already been suggested on this point, with a similar theoretical framework, so this work is not a major breakthrough in understanding the origin of life. But it is still extremely interesting, not only from a chemical point of view, as it confirms that the union of the world of peptides and proteins and the world of RNA, necessary for life to start, is chemically possible in a relatively simple way.

Briones - ARN proteínas (EN)

Carlos Briones

PhD in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, CSIC research scientist at the Center for Astrobiology (CSIC-INTA), where he leads a group researching the origin of life and the development of biosensors, and science communicator.

I find this article very relevant and I liked it a lot. It is of high quality, like all those published by Matthew W. Powner's group, whom I have the pleasure of knowing. The topic raised is fundamental to research on the transition between chemistry and biology, the experimental methods used—both for synthesis and for product analysis—are very elegant, and the results obtained are clear.

It certainly deserves to be published in Nature magazine. In any case, the fact that it took almost a year from submission to acceptance indicates that the peer review process was truly rigorous and thorough. This work will be widely read and cited by the entire international community of scientists working on topics related to the origin of life.

This work is part of one of the most relevant topics in science today: research into the origin of life. Specifically, it focuses on the era known as the “RNA world,” which may have been operational some 4 billion years ago. This would have been the intermediate stage between the prebiotic chemical reactions of systems and the appearance of “modern” cells that already had an established flow of genetic information in the DNA-RNA-protein sense.

According to the RNA World model, the genome of the evolving protocells would be RNA, and some short RNA molecules with catalytic capabilities—called “ribozymes”—would perform the biochemical functions necessary to establish a primitive metabolism. In the currently accepted version of this model, ribozymes would probably be aided by short amino acid polymers—peptides—that would have formed abiotically, by small organic molecules, and even by certain minerals or metal cations.

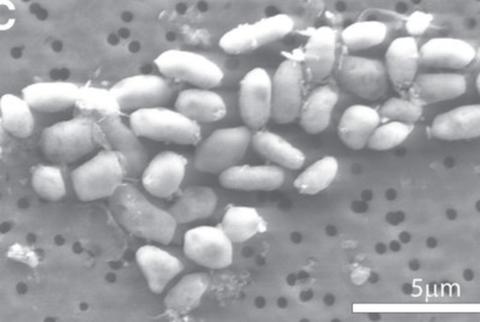

Within this context, the work of Singh et al. considers how transfer RNAs (tRNAs) could have originated through the binding of an activated amino acid to an RNA molecule—a process called “aminoacylation.” This is a step that was required before the origin of the translation of genetic information contained in RNA into proteins. The main challenge was that, until now, it had not been possible to achieve this selective aminoacylation of RNA in water.

The article demonstrates that aminoacyl thiols or amino acid thioesters—that is, amino acids bound to sulfur groups—from at least 15 of the 20 amino acids present in proteins can efficiently bind to RNA in water and at neutral pH, without requiring the action of catalytic enzymes. In addition, clear results are also obtained in favor of the polymerization of amino acids from one already bound to RNA, with the consequent formation of peptidyl-RNAs.

In this work, using simple chemistry inspired by current biochemistry—given the involvement of coenzyme A in the formation of thioesters—and compatible with prebiotic conditions, the authors provide a plausible answer to two of the fundamental questions in the synthesis of proteins from RNA, something that nature had to resolve before the appearance of ribosomes: the formation of aminoacyl-RNA and peptidyl-RNA.

The article is well-founded and the results are clearly presented, so no limitations that need to be taken into account have been detected.

However, as is often the case with significant findings, this research raises new questions, which—according to the authors themselves—will be addressed in the group's subsequent articles. One of the most interesting questions is how specific aminoacylation could be achieved between each amino acid and a specific RNA sequence, which would allow the synthesis of 20 different aminoacyl-tRNAs and could be a possible origin of the genetic code.

Singh et al.

- Research article

- Report