For the first time, pig kidneys modified with human renal organoids are transplanted into pigs

An international team, including several Spanish groups and coordinated by the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC), has developed a pioneering technology that allows for the creation of multiple human kidney organoids, their combination with pig kidneys outside the body, and their successful transplantation back into the same animal. The method could contribute to improving future research and, according to the authors, allows us to envision a future clinical scenario in which organs destined for transplantation can be treated and conditioned before implantation. The work is published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

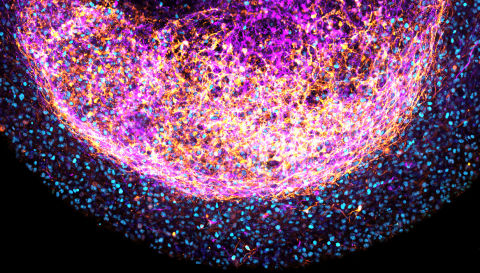

Image of a kidney organoid on day 16 of differentiation obtained by confocal microscopy. / IBEC.

Iván - Cerdos IBEC (EN)

Iván Fernández Vega

Full professor of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Oviedo, Scientific Director of the Principality of Asturias Biobank (BioPA) and Coordinator of the Organoid hub of the ISCIII Biomodels and Biobanks platform

The kidneys are essential organs responsible for filtering between 150 and 180 liters of blood per day, eliminating waste products and maintaining the body's balance of water, salts, and minerals. In the context of transplantation, pathologists assess organ viability using the Banff Score, a system that systematically evaluates all areas of the kidney—glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, inflammation, and vessels—before implantation. This is done through a frozen section histopathological analysis of a renal cortex wedge approximately 1 centimeter in size. This histological analysis allows us to determine the degree of chronic damage and establish whether the organ is suitable for transplantation. When the Banff Score is high, primarily due to glomerular sclerosis, tubular atrophy, or vascular damage, the organ is usually considered non-viable. In this scenario, a technology capable of repairing or regenerating renal tissue before implantation could have an enormous clinical impact.

The article published in Nature Biomedical Engineering is a high-quality and experimentally rigorous work that presents a significant advance in regenerative medicine applied to kidney transplantation. It demonstrates that it is possible to infuse human kidney organoids into live porcine kidneys and, using normothermic perfusion, reimplant them in the same animal without known pathology, verifying that the human cells remain viable and integrated, without causing rejection or significant tissue damage. The research stands out for offering a scalable and reproducible method to generate thousands of organoids, which opens the door to conditioning organs ex vivo before transplantation.

From a pathological and clinical perspective, this approach could, in the future, improve the quality of kidneys with a high Banff score, prolong the lifespan of grafts, and reduce the number of discarded organs. However, this has not yet been experimentally demonstrated, and there is no evidence that the organoids can participate in repair or connect to the afferent and efferent arterioles necessary to restore filtering function.

The work, therefore, has enormous value as a proof of concept, but its results should be interpreted with caution. The experiments were performed on seven perfused kidneys, with follow-up limited to 48 hours, so the long-term effects and the immunological or proliferative behavior of the human cells over longer periods are still unknown. After the transplants, the animals were sacrificed, and a detailed histopathological analysis of the reimplanted kidneys was performed, but not a complete autopsy that would have allowed for the identification of possible cell dissemination to other organs. Although no complications were observed, questions remain regarding possible microemboli, local inflammation, or uncontrolled cell proliferation that could lead to tumors in the long term.

Overall, this is a solid, innovative, and well-designed article that points in a promising direction at the frontier between bioengineering and kidney transplantation, although it is still in an early experimental phase. If further studies confirm its safety and efficacy, it could open the door to regenerative strategies capable of recovering damaged organs and facilitating their use in human transplantation.

Conflict of interest: "I declare that I have collaborated within the institutional framework of the Biomodels and Biobanks Platform of the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII), coordinated by Drs. Elena Garreta and Núria Montserrat, and in which Dr. Alberto Centeno acts as co-leader of the Animal Models Hub. I have maintained a professional scientific collaboration with them for three years, without any economic or contractual link that has influenced my assessment of this work".

Matesanz - Cerdos IBEC (EN)

Rafael Matesanz

Creator and founder of the National Transplant Organisation.

This is undoubtedly an excellent article, the result of collaboration between several Spanish and international institutions, led by the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia, on the topic of organoids, which have great future potential.

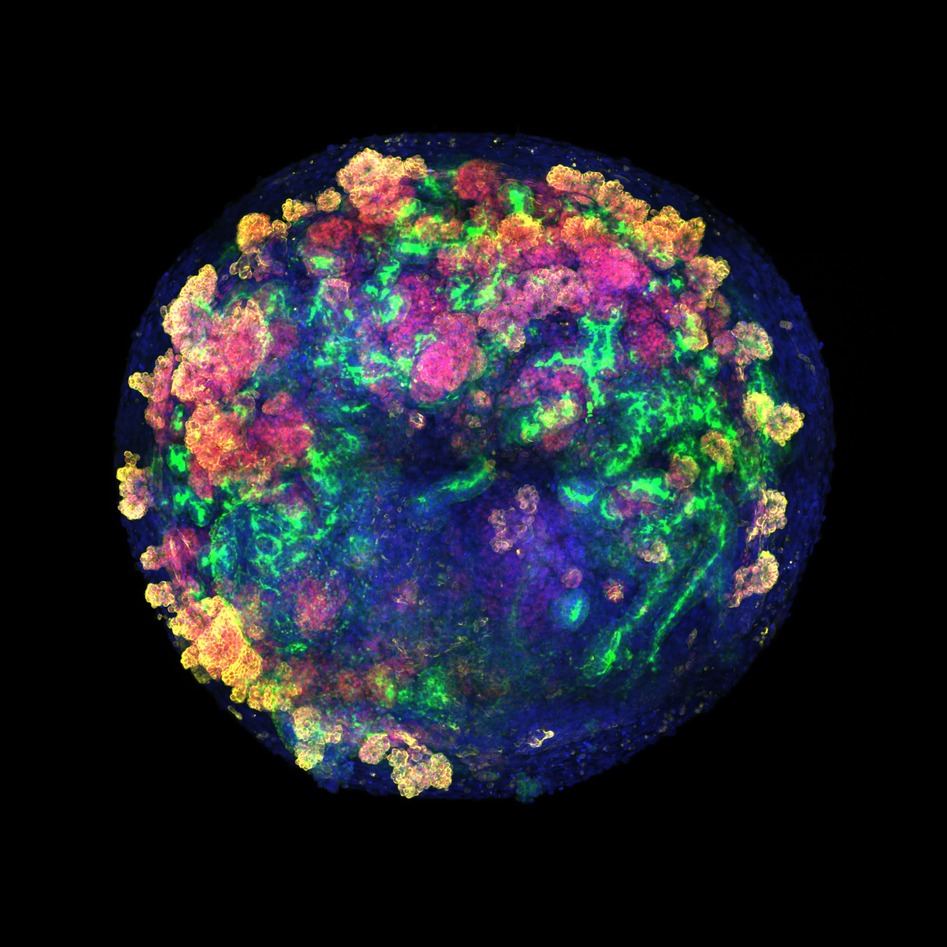

Organoids are reduced and simplified versions of a human organ, grown in the laboratory. They are composed of different cells organized into small, three-dimensional structures, ranging in size from microns to centimeters, similar to living tissues or organs, in this case, the kidney.

Although there are various ways to produce them, starting from different cell types, those of most interest to us for this type of transplantation study are those generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). However, one of the main problems until now has been the difficulty of generating them in a simple and reproducible way.

The greatest value of this article is probably its first-ever description of a systematic and scalable method for producing these human kidney organoids in significant quantities and affordably, using microaggregation techniques and genetic engineering. The procedure described here could be highly useful in future research.

Regarding the second part of the article, the attempt to make these organoids suitable for transplantation, it's important to remember that the biggest problem is that, to date, we haven't been able to get them to develop an adequate blood vessel structure. Therefore, they can be used for drug testing, studying organ development, or other applications, but not for transplantation. For this reason, the approach of this work is original and potentially valuable for future research, as it successfully infuses human kidney organoids into porcine kidneys using normothermic perfusion machines commonly used in clinical practice.

The researchers achieved a breakthrough: after transplanting these modified porcine kidneys into other pigs, the infused human organoids remained integrated into the porcine kidney tissue, maintaining its viability and without triggering significant immune responses. This could pave the way for a procedure to repair kidneys and improve their viability before transplantation.

It goes without saying that this part of the study is in the preclinical phase and is still very early, but the readily available and abundant supply of these kidney organoids could accelerate their transition to clinical practice, apart from the fact that the use of perfusion machines allows them to be introduced into the renal parenchyma and the changes induced by them in the kidney "under repair" to be perfectly evaluated.

Garreta et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Experimental study