A device improves vision in people with age-related macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of irreversible blindness and there is no treatment that can restore vision. Now, an international team has tested a device that combines a small wireless chip implanted in the back of the eye with high-tech glasses. The scientists have managed to partially restore vision in people with an advanced form of the disease. Specifically, 26 of the 32 people who completed the trial had clinically significant improvement and were able to read. The results are published in the journal NEJM.

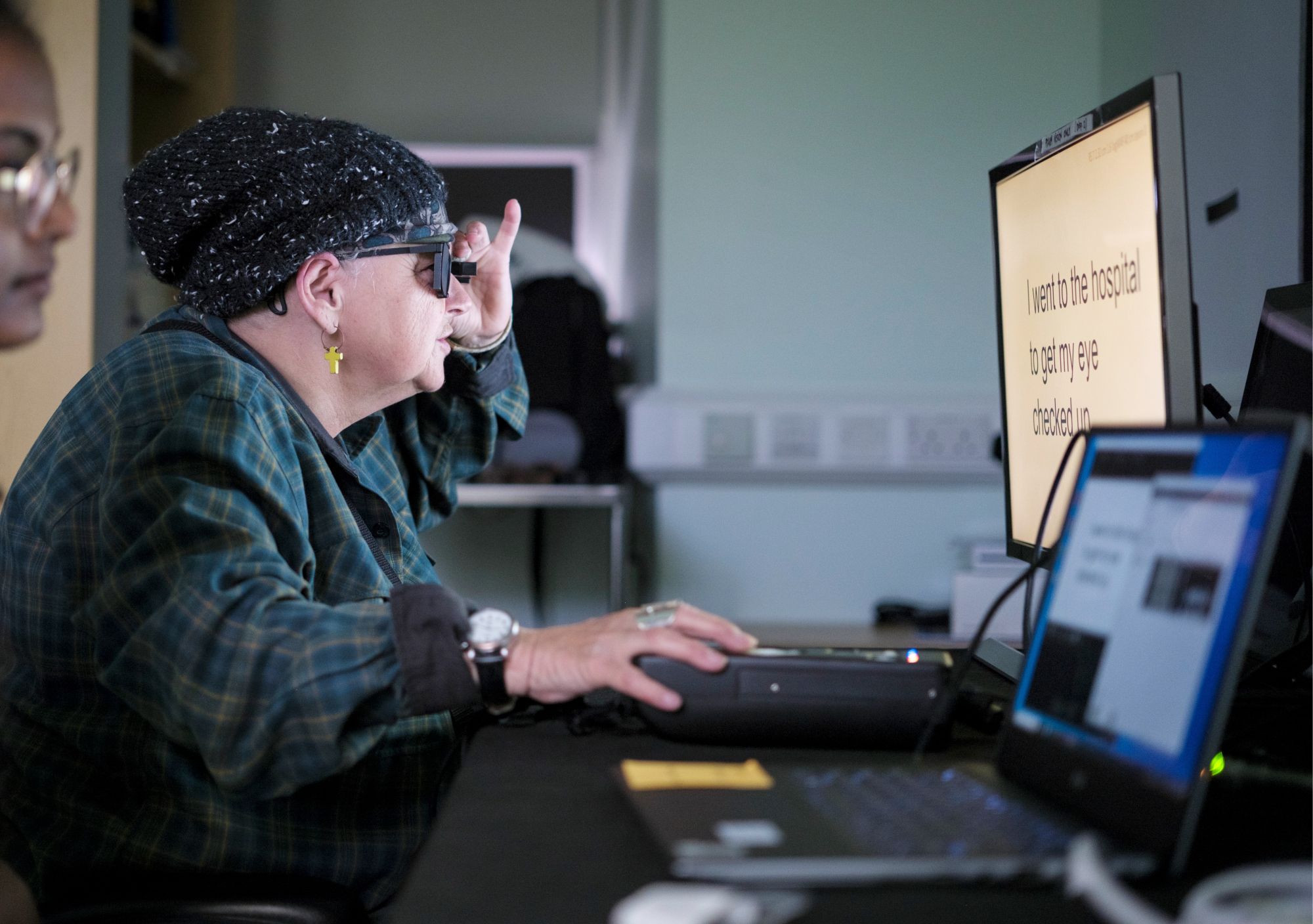

Study partipant Sheila Irvine, a patient at Moorfields, training with the PRIMA device. Credit: Moorfields Eye Hospital.

Conchi Lillo - prótesis DMAE EN

Conchi Lillo

Head of the Degenerative Disorders of the Visual System group at the Castile and León Institute of Neuroscience and professor at the University of Salamanca

This work is funded by Science Corporation, formerly known as Pixium Vision, which developed retinal stimulation devices several years ago. In those early devices, which have been used in several laboratories around the world and worn by patients for several years, the microchip was implanted in people who had lost their photoreceptors due to various problems, but it was implanted in an area close to the retinal ganglion cells (the last relay within the retina), so the vision generated was ‘poorer’ than that obtained with the current system. Since then, they have been trying to improve the technology to stimulate a layer of cells above, the bipolar cells, which receive information directly from the photoreceptors (which these patients have lost) and thus gain ‘resolution’. In other words, they gain a layer of retinal information.

This new device, called PRIMA, is a major advance in retinal neurostimulation, as AMD is currently the leading cause of irreversible blindness and there are currently no therapies that restore vision or cure it. To date, approved therapies only seek to slow the progression of degeneration, not restore lost vision.

Previous retinal prostheses (there is one called ARGUS) were mainly limited to providing light sensitivity and had very low resolution (those implanted near the ganglion cells), while PRIMA focuses on restoring functional vision of shapes and patterns. Not only that, but according to the study, through the digital enhancements added to the glasses (zoom and contrast), participants in the clinical trial achieved visual acuity of up to 20/42, exceeding the theoretical resolution that the implant itself is supposed to generate (20/400). The success of this new PRIMA device could open the door to testing it in patients with other types of blindness caused by photoreceptor loss, such as retinitis pigmentosa.

As for the limitations, I believe that, although this is an important advance in this technology, there are several:

- It should be noted that these people will not be able to fully recover their visual quality (they cannot achieve the same type of vision they had before). According to the study, it has only been possible to provide them with black and white vision, without intermediate shades of grey. This limits their ability to perform complex visual tasks. Facial recognition, for example, requires a grey scale and is something that patients requested, as was the ability to read.

- Another issue is that, according to the study, there were several problems associated with the subretinal surgery required to perform the implant (retinal atrophy increased in many patients). It is a very complex procedure, so it is common for there to be problems associated with it.

- Finally, there is the issue of time. People with AMD are usually elderly patients, so although any repair is beneficial, they require short-term assistance (the study indicates that, unfortunately, three of their patients died during the trial). These trials are conducted on people who have lost a lot of visual capacity, as it would be very dangerous to subject people in the early stages of AMD (i.e., with fairly good visual quality) to such risky procedures, because they could lose more visual capacity than they could gain with the implant. Furthermore, according to the study, although patients were able to ‘see patterns’ five weeks after the procedure, adapting to the information they receive requires many months of training. The main study focuses on the results at 12 months, although a follow-up of up to 36 months is planned to determine the long-term viability of the implant.

Holz et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People