First results on babies born with pioneering technology that reduces risk of mitochondrial disease

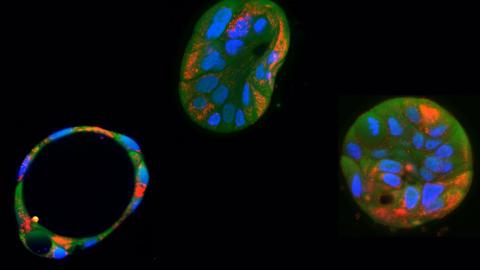

In 2015, the United Kingdom became the first country to pass legislation allowing the use of mitochondrial donation technology, pronuclear transfer. The technique is designed to limit, through in vitro fertilization, the transmission of mitochondrial DNA diseases in babies born to women who are at high risk, and for which there is no cure. Two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) describe the results of the first treatments performed to date, from which eight babies have been born by mitochondrial donation, with reduced risk of disease.

Lluis Montoliu - mitocondrias

Lluís Montoliu

Research professor at the National Biotechnology Centre (CNB-CSIC) and at the CIBERER-ISCIII

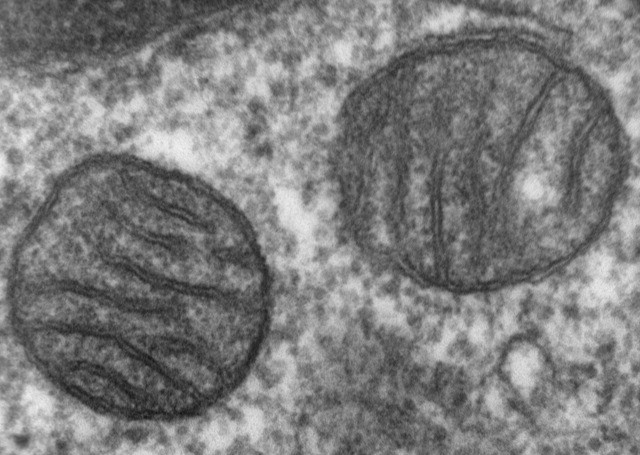

In 2016, John Zhang, a medical specialist from an assisted reproduction clinic in New York called the “New Hope Fertility Center,” crossed the border into Mexico to carry out a procedure that was prohibited in the U.S. and not yet regulated in Mexico. A couple from Jordan had come to this clinic in hopes of having viable offspring. The couple had previously had two children who had died due to Leigh syndrome, one of several mitochondrial diseases that are usually devastating and have no cure. Mitochondria (our energy factories) are generally inherited from the mother, through the egg. The mother had approximately 25% of her mitochondria affected, which were the ones she had passed on to her two deceased children.

Dr. Zhang did not use the procedure that had been pioneeringly approved in the United Kingdom, due to the Muslim religion of the couple, which opposed the destruction of human embryos. Instead, he opted to extract the nucleus from the mother’s egg (technically the metaphase plate, an incomplete nuclear division stage in which all eggs ready to be fertilized are found) and transferred it into the egg of another woman (with healthy mitochondria), from which the nucleus had also been removed. Once the mother’s nucleus was transferred to the second woman’s egg, he used the resulting egg for in vitro fertilization with the father’s sperm to create embryos. Dr. Zhang created five embryos this way, of which only one developed normally. It was implanted into the mother’s uterus and resulted in the birth of a healthy baby. This was the first baby born using the “three-parent technique”: two mothers and one father.

In the United Kingdom, the British Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) had approved in 2015 another technically different procedure—also called the “three-parent technique”—to address issues related to mitochondrial diseases. In this case, the father’s sperm is used to fertilize (via intracytoplasmic sperm injection, or ICSI) two eggs: one from the mother carrying the affected mitochondria, and one from another woman with healthy mitochondria. After fertilization begins, two pronuclei (one from the father and one from the mother) appear transiently and are destined to fuse and form the first nucleus of the zygote. Before this happens, researchers can extract the two pronuclei from the fertilized egg created with the mother’s egg and the father’s sperm, and transfer them to the egg of the second woman, also fertilized with the father’s sperm, from which the pronuclei have been removed. The final result is that the egg with the healthy mitochondria from the donor woman now contains the two pronuclei from the couple, and their baby is born free of mitochondrial disease and is genetically their child. The healthy mitochondria come from the donor woman. This method, which is somewhat more aggressive but less risky than the previous one, involves destroying one embryo to create another—something the Muslim couple treated by Dr. Zhang found unacceptable. The first baby born in the United Kingdom through the officially approved British three-parent procedure was born in 2023.

Ten years after the technique was approved in the UK, a team of British and Australian doctors and researchers published this week in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) the results of applying the British three-parent technique to 22 women who carried pathogenic mutations in their mitochondria (and were therefore at high risk of having children with these incurable diseases). Of the 22 women treated, only 8 gave birth (36%), and one more pregnancy is still ongoing. The eight babies born are healthy, with no signs or only very low levels of affected mitochondria—levels not sufficient to cause disease. So far, the eight children are doing well. Only a couple of them developed minor clinical issues, apparently unrelated to the procedure, which resolved either through treatment or spontaneously.

Additionally, the researchers applied a second technique (preimplantation genetic testing, or PGT) to women who had heteroplasmy (a mix of healthy and affected mitochondria) to assess the percentage of affected mitochondria in embryos obtained through in vitro fertilization and to select those with lower levels of affected mitochondria. In this case, they achieved 16 pregnancies among 39 women (41%), resulting in 18 babies born with less than 7% of affected mitochondria.

In Spain, Law 14/2006 of May 26, on assisted human reproduction techniques, does not explicitly refer to this technique (which didn’t exist when the legislation was passed), so strictly speaking, the procedure is neither expressly prohibited nor explicitly authorized in our country. Essentially, it is not regulated. The legal and ethical uncertainties that remain have so far prevented the three-parent technique from being used in Spain.

However, this new study shows that the technique has a notable success rate (36%) and could well be offered to couples in which the mother carries affected mitochondria, to allow them to have children free from terrible mitochondrial diseases. Personally, I believe we should allow this technique in our country in those assisted reproduction clinics that are properly trained in this sophisticated embryonic intervention methodology.

Nuno Costa-Borges - NEJM 8 bebes donacion mitocondrial

Nuno Costa-Borges

Researcher and embryologist, scientific director and CEO of Embryotools, Parc Científic de Barcelona

As a pioneering center in mitochondrial replacement therapies (MRT), Embryotools welcomes the recent publication by Hyslop et al. in The New England Journal of Medicine, reporting outcomes from pronuclear transfer (PNT) to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) disease. The study reports the birth of eight babies—four girls and four boys, including one set of identical twins—born to seven women at high risk of transmitting severe mtDNA disorders. Importantly, all infants are healthy and show no signs of mitochondrial disease. However, the detection of low-level postnatal mtDNA heteroplasmy (“reversal”) in 3 of the 8 infants (5%–16%) deserves particular discussion.

Due to UK regulations that prohibit testing for heteroplasmy in embryos, the timing of this reversal could not be pinpointed. Their analysis relied on arrested embryos and blood samples from newborns, which limits interpretation. In contrast, our recent pilot trial using maternal spindle transfer (MST)—a form of MRT where mitochondrial replacement occurs in the oocyte before fertilization—in infertile patients led to seven live births, two of which also showed reversal, a comparable frequency. However, our approach included direct assessment of heteroplasmy in blastocysts and, longitudinally, in multiple tissues including amniotic fluid. This allowed us to accurately define that reversal occurred between the blastocyst stage and mid-gestation (~15 weeks), reinforcing the importance of prenatal testing to detect reversal early and guide clinical decision-making. In our study, all infants are also healthy and have been followed up showing no adverse events.

This phenomenon—mtDNA ‘reversal’—has previously been described in human cells in vitro but not in MRT-derived children. Minimal levels of maternal mtDNA carryover can expand substantially, potentially compromising the efficacy of MRTs to prevent mitochondrial disease. The biological mechanisms underlying this selective amplification remain unclear but appear to occur early in development, and instances may therefore be detectable using prenatal testing. It is worth noting that the impact of mtDNA reversal in infertility treatments is likely less concerning, as maternal mtDNA in these cases does not carry pathogenic mutations. Moreover, with appropriate matching of mtDNA haplotypes between the mother and donor, the biological consequences of low-level heteroplasmy could be further minimized or even rendered clinically irrelevant.

Currently, only the UK and Australia have regulated the use of MRT to prevent transmission of mtDNA mutations. We believe that other countries should adopt similar regulatory models. In particular, MRT should also be contemplated for infertility treatment. Infertility is a disease recognized by the WHO, and MRT can offer a genetic link to the mother for patients who would otherwise rely on egg donation. This justification aligns with the ethical principles underpinning MRT for disease prevention. As a pioneer group in this technology, Spain should lead in regulating these applications to ensure patient safety and prevent reproductive tourism to countries where such techniques may be offered without appropriate oversight.

In light of these findings, we reaffirm the urgent need to continue performing well-regulated, larger, long-term studies to fully evaluate the safety, efficacy, and clinical implications of MRTs. Ongoing research under appropriate oversight is essential to ensure the responsible development of these technologies, improve genetic counseling, and support informed decision-making by patients and clinicians alike.

We also advocate for thoughtful regulatory evolution that upholds patient autonomy, scientific excellence, and the principle of reproductive justice.

Calonge - mitocondrias

Rocío Núñez Calonge

Scientific Director of the UR International Group and Coordinator of the Ethics Group of the Spanish Fertility Society

A team from Newcastle University (UK), led by Dr. Louise A. Hyslop, has published the first clinical results of the use of mitochondrial donation to prevent the transmission of hereditary mitochondrial diseases in The New England Journal of Medicine. Thanks to this technique, eight babies have already been born, marking a milestone in reproductive medicine.

Each year, about 1 in 5,000 babies are born with mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which can cause devastating diseases by affecting energy-intensive organs such as the brain, heart, and muscles. These diseases, which are transmitted exclusively through the mother, are often fatal and, until now, had no cure.

The technique used, known as pronuclear transfer—legal in the United Kingdom since 2015—involves extracting the pronuclei from the fertilized egg of the surrogate mother and transferring them to a donated egg with healthy mitochondria, from which the nucleus has been previously removed. This allows the embryo to retain the nuclear DNA of the parents, but with functional mitochondria from the donor.

The results are encouraging: in six of the eight babies born, the presence of pathogenic mtDNA variants was reduced by more than 95%; in the other two, the reduction was 77% to 88%. This demonstrates that the technique is effective in reducing the transmission of these serious hereditary diseases.

However, the study also raises ethical and scientific questions. The combination of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from different people could have long-term effects that are still unknown. For this reason, the researchers stress the need for rigorous follow-up of these children, which in this case will continue until they reach the age of five. In addition, they insist that this procedure should only be used when there are no other viable reproductive alternatives.

This breakthrough represents new hope for many families affected by mitochondrial diseases. However, it also calls for caution, transparency, and a broad ethical debate on the limits and responsibilities of genetic medicine.

Restrepo - mitocondrias

Santiago Restrepo Castillo

Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas at Austin (USA)

Mitochondrial diseases are a group of chronic metabolic disorders that can be fatal. These diseases are caused by mutations in the human genome, which consists of nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA. In particular, metabolic disorders caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA, which affect one in five thousand people, are maternally inherited and currently incurable. In recent years, there have been major advancements in the development of strategies for the treatment or prevention of genetic disorders caused by mutations in nuclear DNA. In contrast, similar strategies for diseases caused by alterations in mitochondrial DNA have remained largely understudied.

Aiming to establish a preventive strategy for metabolic diseases caused by mitochondrial DNA mutations, the authors of this pair of studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine developed an integrated program of preimplantation genetic testing and pronuclear transfer (PGT and PNT, respectively). In this program, female patients carrying mitochondrial mutations underwent PGT to identify embryos with low levels of mitochondrial DNA mutations. In cases where an embryo with these characteristics was identified, the embryo was implanted in the patient and the course of the pregnancy was monitored. In addition, in cases where it was not possible to identify embryos with low levels of genetic alterations, the patients underwent PNT, a procedure in which mitochondrial DNA without mutations is obtained from a donor.

Encouragingly, through this integrated PGT and PNT program, at the time of publication, the authors have already demonstrated a significant reduction in the maternal transmission of mitochondrial mutations in eight cases. Furthermore, the children born from these cases have shown normal development.

In conclusion, this study represents a major advancement in the field of medical genetics and genomics. Understanding the current limitations of mitochondrial gene editing, which would allow genetic alterations to be corrected in different contexts, the authors chose to explore a procedure that cuts the problem off at the root by preventing the transmission of the mutated genetic material. Furthermore, this pair of studies demonstrates clinical benefits in children who, without the integrated PGT and PNT program, would likely have been born with debilitating or fatal genetic mutations. It will be exciting to see if the benefits are maintained over time, and it will be critical to further develop this integrated process to increase its success rates.

Mertes - mitocondrias

Heidi Mertes

Associate Professor in Medical Ethics, Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Ghent University, Belgium.

I am happy to see that the first results from the Newcastle University group are now finally published, after being granted a license by the HFEA in 2017, and that the eight resulting children are in good health. However, while the results show that the technique is feasible and can lead to a substantial reduction of the mutation load in the resulting children, it also shows that we need to tread very carefully.”“In line with previous research by the group of Nuno Costa-Borges, this research confirms the possibility of reversal (meaning that although there is only a small fraction of the intended mother’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the embryo, this fraction sometimes increases substantially as the foetus develops), which could still result in mitochondrial diseases in the resulting children. Fortunately, preliminary research does indicate that while the mutation loads appear to increase between the embryonic phase and birth, they appear to remain stable after birth.”“These are very important results as there was a lot of uncertainty over the safety of MRT. Using PGT when possible and reserving MRT for those cases in which PGT cannot offer a solution was a prudent approach given the experimental nature of MRT. It will be interesting to see more data in the future on whether reversal is more frequent in MRT or PGT, so that the safest procedure can be selected.”“Although the heteroplasmy-levels are limited in this study, it does show that reversal is a real danger for the offspring, which can have serious health implications. At least three things follow from this.”“First, people entering into this and future clinical trials will need to be extensively counselled that this is not a risk-elimination treatment, but a risk-reduction treatment.”

“Second, we need more research into the mechanisms that trigger reversal, so that it can be prevented before this technique is implemented in routine care + We need follow-up research in the children born after MRT.”“Third, it is important to keep in mind that by framing this as a risk-reduction strategy, we are ignoring the possibility of conceiving through a traditional egg donation procedure. While genetic parenthood is evidently important to many people, the trade-off that we are making here is that between a genetically related child with a high risk of mitochondrial disease (natural conception), a genetically related child with a reduced risk of mitochondrial disease (PGT or MRT) and a non-genetically related child with the near-absence of a risk of mitochondrial disease (through donor conception). If people who would have chosen for donor conception now opt for MRT, this is actually a risk-increasing technology, rather than a risk-reducing one.”

“This strategy lowers the risk of mitochondrial disorders in the children when the point of comparison is natural reproduction by the parents, but the safest option is still donor conception, which eliminates the risk of passing on the mitochondrial condition, rather than reducing it.”“While the donor plays an essential role in the birth of the child, attributing them a parenthood-status based on a small genetic contribution appears unwarranted. At the same time it would be correct to call them a ‘genetic progenitor’ or ‘genetic contributor’.”“While the group of Nuno Costa-Borges received a lot of backlash for performing their MRT clinical trial in people with repeated IVF failure, rather than people with mitochondrial diseases, we must acknowledge in hindsight that given the phenomenon of reversal, their approach might have been the more prudent one. In their study they observed reversal in one infant going from <1% of maternal mtDNA at the blastocyst stage to 30-60% (depending on the tissue type) at birth. This was fortunately not a problem as the maternal mtDNA was not disease-causing, but a similar level of reversal may have devastating consequences in a clinical trial in women with mitochondrial disorders, such as the one reported on in the NEJM today.”

Prokisch - mitocondrias

Holger Prokisch

Head of the Mitochondrial Genetics Research Group, Helmholtz Centre Munich – German Research Centre for Health and Environment, Munich.

The field of mitochondrial medicine has been eagerly awaiting the results of this study. The robust data describe a real breakthrough for women with a (nearly) homoplasmic pathogenic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variant in terms of their ability to probably have healthy genetically related children. The risk of the children to develop the disease after preimplantation genetic testing is minimal. All gene variants tested require very high heteroplasmy for the disease to manifest, or are typically homoplasmic.

There is an observation in the literature that in a few cases, the mother's mutated DNA is revised. Interestingly, this also involves an LHON mutation (Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy) [Nature 2019, Nature 2016], which is almost always homoplasmic in the population and, according to recent data, has a low penetrance of less than five percent for LHON disease (only five percent of gene carriers also develop the disease; editor's note). In this respect, the selection of mutation carriers for this study with four LHON mutations is not entirely fortunate. The homoplasmy of the LHON variants suggests that they may offer a selective advantage. Since mitochondrial transfer does not eliminate the mutation, there is a risk that the mutation will be passed on to the next generation. This often leads to significant shifts in heteroplasmy, sometimes to the detriment of patients. However, disease-causing variants tend to have a selection pressure.

Human studies show no risk of incompatibility between the donor mtDNA and the parents' nuclear DNA.

There is no newborn screening for mitochondrial DNA mutations. Women are identified as mutation carriers when they or one of their children develop the disease. Prediction or risk assessment for the next generation is difficult for mtDNA mutations in the mother. Many centers for mitochondrial diseases work with the group in Newcastle to provide information about the options available there or to offer preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

Larsson - mitocondrias

Nils-Göran Larsson

Group Leader "Maintenance and expression of mtDNA in disease and ageing", Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska-Institut, Stockholm, Sweden.

The study in NEJM is very important and represents a breakthrough in mitochondrial medicine. It should be remembered mitochondrial diseases can be devastating and cause substantial suffering in affected children, sometimes leading to an early death. Families are profoundly affected and the paper in NEJM describe how birth of affected children can be prevented by mitochondrial donation. This advanced procedure is not a disease-treatment but rather an intervention that minimizes the transmission of mutated mtDNA from mother to child. For affected families this is a very important reproductive option. The paper describes a relatively small series of 8 babies born after mitochondrial donation by pronuclear transfer. The paper is carefully done and of very high quality but as always in science the results need to be confirmed by independent studies. Also, long-term clinical follow-up studies of born babies will give additional information about the safety and efficacy of mitochondrial donation.

Before this procedure was applied to human reproduction there was a very long development and evaluation process. There has been a lot of constructive discussion in the scientific community, and the UK Parliament approved legislation allowing mitochondrial donation in 2015.

Mitochondrial donation by the pronuclear transfer procedure always leads to carry-over of some mitochondria from the mother and mutant mtDNA can be transferred. The data presented in the NEJM paper shows that mutant mtDNA was not detected in blood of 5 of the born children. However, in three children, low levels of mutant mtDNA were detected in blood. These low levels of mutant mtDNA are unlikely to cause mitochondrial disease but additional follow-up studies are needed. As pointed out by the authors, the mitochondrial donation by pronuclear transfer should be regarded as a risk-reduction strategy. As always, when it comes to new medical procedures there is a need for validation by independent studies. Also, additional long-term follow-up studies of children born after mitochondrial donation will be needed.

The authors report that the transferred mtDNA has no mutations and the donor mtDNA is therefore unlikely to cause disease or impact ageing. During normal ageing, mtDNA acquires mutations (somatic mutations), e.g., during the massive cell division when the embryo is formed and develops. These mutations are typically present at low levels but accumulate to high levels in a subset of cells in many different ageing tissues. The mitochondrial donation involves transfer of mtDNA without mutations and there is no reason to believe that the donor mtDNA will additionally impact the ageing process.

When it comes disease-causing mtDNA mutations that are present in all copies (i.e., homoplasmic mtDNA mutations) there is currently no alternative to mitochondrial donation to prevent transmission of mutated mtDNA from mother to child. It is possible that alternate methods will be available in the future, e.g., correction of mutant mtDNA by gene editing techniques. There are currently a few promising pharmacological therapies for mitochondrial disease, e.g., nucleoside therapy for mtDNA depletion disorders. It is likely that more treatments will be available in the near future because this field is rapidly developing

Thornburn - mitocondrias

David Thorburn

Co-Group Leader of Brain & Mitochondrial Research at Murdoch Children's Research Institute and the University of Melbourne.

Mitochondrial donation was legalised in the UK in 2015 and in Australia in 2022. It was clearly a complex process in the UK to develop the approvals processes, the clinical and lab pathways, cope with delays from COVID-19 and accumulate sufficient outcomes to publish them without impinging on the privacy of the families involved.

So it is very exciting to see the first publications describing results for the first eight babies born in the UK program. The initial results demonstrate that the approach is effective in reducing the risk of having a child with mitochondrial DNA disease for women who are at high risk. For about three quarters of couples participating in the pronuclear transfer method, at least one suitable embryo was generated. About 40% of these couples had a baby and all were healthy and had undetectable or low levels of the abnormal mitochondrial DNA. Three babies had short-term symptoms that resolved and did not appear to relate to mitochondrial disease. All babies are developing normally to date, with the oldest 5 years of age.

The studies emphasise that longer-term followup needs to be performed, and the efficiency of the method could be further improved to achieve higher pregnancy rates. They demonstrate the value of offering the program in conjunction with other reproductive options, such as pre-implantation genetic testing, which can be effective in women with lower risk. I regard these results as very encouraging and supporting the ongoing development and use of mitochondrial donation in the UK and Australia.

David has declared he has no financial conflicts of interest and has the following unpaid positions: Board Member of the Mito Foundation (the major relevant mito advocacy group) and he played a prominent role in their advocacy for legalising mitochondrial donation in Australia. He is also a Member of the MitoHOPE Executive, funded by the Medical Research Future Fund to deliver an Australian clinical trial of mitochondrial donation.

Koplin - mitocondrias

Julian Koplin

Lecturer in bioethics at Monash University.

It is exciting to see early evidence that mitochondrial donation may be an effective way of increasing the reproductive options of those who are at risk of passing on mitochondrial disorders. These early results are encouraging, though it is important to note that they do not show that mitochondrial donation is risk-free.

Mitochondrial donation's ability to broaden some women's reproductive options should be celebrated. However, it is important that mitochondrial donation continues to be seen as just one option among many, including potentially safer pathways that eliminate maternal mitochondrial DNA risk altogether, like donor egg IVF.

Herbert - mitocondrias

Mary Herbert

Professor of Reproductive Biology at Monash University. She also holds an appointment at Newcastle University and Newcastle Fertility Centre, UK. She is an author on the research.

As a reproductive biologist, I find it enormously gratifying that a new assisted reproductive technology can be used successfully to enable women with very high levels of disease-causing mitochondrial DNA to have children with a greatly reduced of developing the disease.

The findings give grounds for optimism. However, research to better understand the limitations of mitochondrial donation technologies will be essential to further improve treatment outcomes.

In previous lab-based research, we found that carryover of even a small amount of maternal mitochondrial DNA during the pronuclear transfer procedure can increase to very high levels in embryonic cell lines.

For this reason, mitochondrial donation technologies are regarded as risk reduction treatments. Our ongoing research seeks to bridge the gap between risk reduction and prevention of mitochondrial DNA disease.

In the UK, mitochondrial donation treatment is performed within a strict regulatory framework under a licence granted by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. I hope that the successful outcomes reported today will help in navigating the rather complex regulatory system here in Australia.

Mary Herbert Mary is an author of the research.

Rubin - mitocondrias

Eric Rubin

Editor-in-Chief of The New England Journal of Medicine.

These studies unite scientific rigor, clinical innovation, and deep ethical reflection to illustrate the full research continuum from bench to bedside. At the New England Journal of Medicine, we chose to publish this work in its full context, not only to highlight the outcomes, but also to surface the critical questions it raises about translating breakthroughs into patient care.

Where allowed by government regulations, this research has the potential to prevent serious inherited disease and gives parents truly meaningful new options for their children. Its publication also reminds us that preserving the infrastructure and integrity of biomedical research in the US and around the world is essential if we are to continue delivering such transformative treatments to patients.

He is the editor of the journal that published this research.

Bert Smeets - NEJM 8 bebes mitocondrias

Bert Smeets

Professor of Clinical Genomics specializing in mitochondrial diseases, Maastricht University (Netherlands)

These are papers, the scientific community has waited for, for a long time, as they describe the experience of the Newcastle team on pronuclear transfer to prevent the transmission of mtDNA disease, for which they got approval in 2017. The papers describe the current experience in PNT and PGT for preventing the transmission of mtDNA disease. It is good to present a reproductive care pathway, although it is not fully complete and some of the criteria might be reevaluated based on the presented data. The care pathway starts with carriers of mtDNA mutations. I would also include women who have affected children with de novo mtDNA mutations. This concerns about 25% of the mtDNA patients. The recurrence risk is low and generally prenatal diagnosis is offered for reassurance. Furthermore, women with a very low mtDNA mutation load, with skewing mtDNA mutations or large scale deletions could also opt for prenatal diagnosis.

For a reproductive care pathway for mtDNA disease, these groups should be included as well. It is clear that for the remainder according to the HFEA guidelines PNT should only be offered if PGT is unsuitable. It is great that the PNT as an addition to the reproductive choices for mtDNA disease seems to deliver as 8 children without the mtDNA condition were born. However, there are still concerns, as 2 PNT children had a higher mutation load than the carry-over, which means that reversal can occur and could be a risk for having affected children in future treatments. Also, two children had rare medical complications, which according to the authors were not related to the treatment, as this would then be expected for all of them. I do not think that is true as technical variation occurs and donors will be different. It is good to carefully monitor this, as one of the aims of HFEA guided clinical application is to find-out if PNT by itself is safe, not only to prevent mtDNA disease. The discussion on this is not very strong.

Finally, a key unanswered question is why it took so long to come out with these results. Eight births with no mtDNA disease in 7 years deviates largely from the expected150 yearly births, as described by the same group in NEJM in 2015, if all women would opt for this procedure. It seems that the children born are quite recent (only one >18 months), so one wonders if there is a learning curve, change in procedure or whatsoever, explaining the increasing success rate. It would be fair to discuss this in more detail as it would make it much clearer and more realistic which women of the target group will benefit from MD. And that is still a positive message.”

Conflict of interest: "I am scientific advisor for the HFEA on PNT applications".

Lee Chung-Hsi - NEJM 8 bebes mitocondrias

Lee Chung-Hsi

Professor, Graduate Institute of Health and Biotechnology Law, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Advancing with Cautious Innovation and International Consensus. While early clinical results show promise in reducing the level of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA in newborns, the application of Pronuclear transfer (PNT) raises significant ethical and regulatory questions that must be addressed through both national oversight and international dialogue. From a bioethical standpoint, germline modification—defined as altering genetic material in a way that affects future generations—has long been met with caution. This is because it involves irreversible changes to the human genome, with potential consequences not only for the individuals born from such interventions but also for society’s understanding of what it means to be human.

Pronuclear transfer, however, occupies a unique space in this debate. It targets mitochondrial DNA, which, although essential for cellular energy production, contributes relatively little to traits traditionally associated with identity, such as physical appearance, personality, or intelligence. Because of this limited influence on key phenotypic characteristics, PNT is viewed by some as an acceptable “ethical testing ground” for germline-level intervention. Rather than resorting to high-risk gene therapy after the onset of a hereditary disease, using PNT technology to reduce the likelihood of disease is a more ethically acceptable option. It provides a possible pathway to explore the responsible use of reproductive technologies without crossing the bright-line boundaries typically drawn around nuclear DNA modification.

Nonetheless, mitochondrial DNA modification is not without ethical complexity. Even if its direct functional role is narrower, it still involves heritable changes and the creation of embryos with genetic contributions from three individuals—the intended mother and father, and a mitochondrial donor. This raises questions about identity, kinship, and the rights of the resulting child, especially regarding disclosure and autonomy. Moreover, the long-term health effects of such interventions remain unknown. To prevent a gradual erosion of ethical boundaries, transparent ethical review processes and long-term clinical monitoring must be established as foundational requirements for any country considering the use of PNT.

From a clinical perspective, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) should remain the first-line option for reducing the risk of mitochondrial disease transmission. PGT is a more established and less invasive method that allows for the selection of embryos with minimal or undetectable levels of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA. In many cases, this approach has proven effective and carries fewer biological and ethical uncertainties than PNT. In contrast, PNT is a more complex and experimental procedure that combines nuclear DNA from the parents with mitochondrial DNA from a donor egg, and it may result in lower fertilization rates or higher embryonic loss. Therefore, in keeping with the precautionary principle in bioethics, PNT should be considered only when PGT is not feasible or has been shown to be ineffective.

The United Kingdom currently leads in the clinical implementation of PNT, having established a strict licensing and regulatory regime through the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). The UK’s model reflects a commitment to enabling scientific advancement while maintaining ethical vigilance. However, reproductive technologies such as PNT are inherently transnational. If only a few countries offer access to such procedures, it may prompt “reproductive tourism”, whereby patients travel abroad to seek unregulated or less strictly governed treatments, potentially undermining safety standards and ethical norms.

For this reason, a coordinated international approach is urgently needed. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Medical Association (WMA) are well-positioned to initiate global discussions and help formulate shared ethical guidelines and governance frameworks. These discussions should encompass not only scientific and medical dimensions but also social, cultural, and legal implications. Establishing minimum ethical standards and oversight mechanisms will help ensure that the benefits of PNT are pursued responsibly and that global health equity and ethical integrity are preserved.

Hyslop et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

McFarland et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed