Two changes in the human pelvis that were key to walking on two legs discovered

The upper part of the human pelvis, the ilium, underwent two major structural changes during evolution that enabled humans to walk on two legs. One was the formation of cartilage and the second was the process of bone formation. New research identifies differences in the way bone cells are deposited on cartilage in the human ilium, compared to other primates and human long bones. The study, published in Nature, lays the genetic and evolutionary foundations for bipedalism, according to the authors.

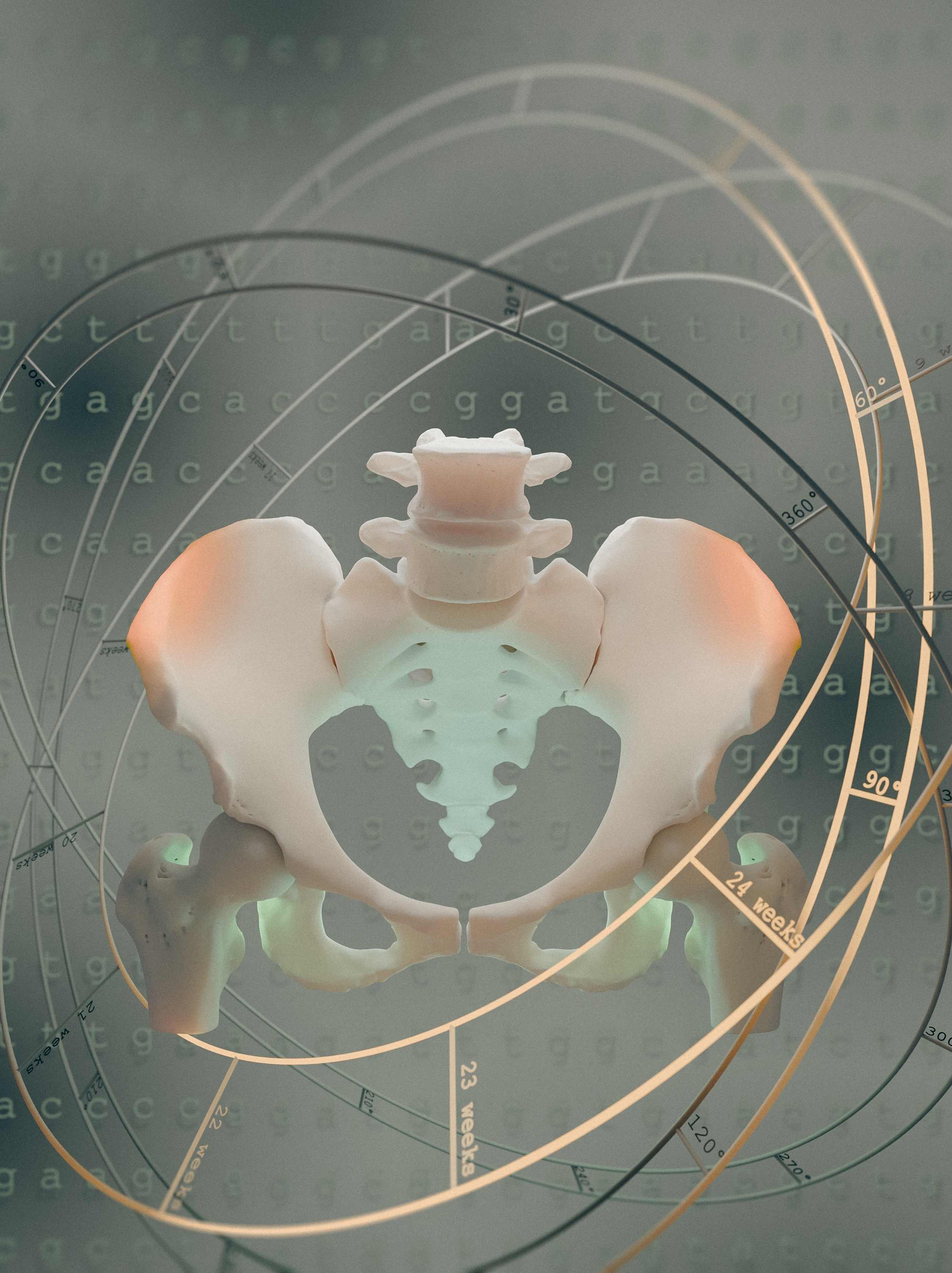

Caption: The evolution of the human pelvis in time and space. The axes depict the angular (heterotopic) shifts in growth plate orientation and the temporal (heterochronic) shifts in bone formation critical to human pelvic form. Credit to Dr. Behnoush Hajian.

Juan Manuel Jiménez Arenas - pelvis humana EN

Juan Manuel Jiménez Arenas

Full Professor in the Department of Prehistory and Archaeology

Head of ProyectORCE

Does the press release accurately reflect the study?

‘Yes, in fact, I would say that it is a conservative press release, since it focuses on the aspects most supported by the experiments and the resulting data generated by the research team. For example, the part dedicated to what it contributes to the evolution of hominins is completely omitted.’

Is the study of good quality?

"Without a doubt, this is an article of enormous quality and relevance. Although bipedalism, due to its uniqueness among primates, has been considered a characteristic closely linked to the evolutionary history of humans, many of the mechanisms underlying this complex change (which has affected all parts of our body) remain hidden. However, studies such as this one make a solid contribution to expanding our knowledge of our particular mode of locomotion.

The conclusions are supported by solid data that also comes from different disciplines. This “interdisciplinary” approach gives this work both robustness and originality. The histological (tissue) and genetic analyses give this work an incredible level of detail.

I would like to highlight three aspects. The first is that it is not necessary to study fossils of our ancestors to understand how a particular anatomical feature or, as in this case, a function has evolved. Work such as this demonstrates that by asking the right research questions and using the appropriate methodologies, much progress can be made in understanding processes that occurred in the past. The second is that embryonic development provides clues to understanding the bone morphologies of adult individuals. The third is that experimentation involving genetic modifications applied to other animals, in this case mice, is a fundamental tool for understanding the specificities of humans. And finally, that certain genetic disorders whose symptoms include the expression of morphological characteristics that can be considered ancestral are also fundamental to understanding ourselves as we are now.

How does this work fit in with existing evidence?

"A good scientific article, such as this one, should not only fit in with what is already known but also challenge what has been previously established. In this sense, the origin of bipedalism had been linked to multiple factors. The aridification and opening up of open spaces to the east of the Rift Valley; the reduction in the energy cost of locomotion; less exposure to the sun; etc. All of these are linked to the East Side Story.

However, one of the most plausible hypotheses today is that bipedalism originated in suspensory locomotion (using the arms) and orthograde locomotion (with the spine straight) by the common arboreal ancestor of chimpanzees and humans—something similar to what is observed in today's orangutans.

Following this hypothesis, we should consider human bipedalism and that of other fossil hominins as a more ancestral system of locomotion than that of chimpanzees. However, from a morphological and genetic point of view, this new article highlights that there are significant differences between the pelvis of humans and that of the other primates studied. Thus, the transition from orthograde locomotion, in which the upper limbs predominated, to another in which the lower limbs, the legs, predominate, must have involved important new developments.

Are there any important limitations to consider?

"The greatest limitations are linked to the three-step proposal for applying the results of this study to hominin evolution. The scarcity of fossils and the practical impossibility of carrying out histological and genetic analyses on the few pelvises that mark the eight million years of hominin evolution reduce the probabilities and possibilities of testing this proposal. However, the discovery of new fossils and methodological developments may contribute to unravelling the secrets of the evolution of bipedalism and to supporting, qualifying or rejecting this hypothesis (the three-step hypothesis: the two steps related to how the iliac bone of the pelvis develops and is therefore formed, and the step related to the delay in ossification).

On the other hand, it does not take into account that in the period between five and two million years ago, there are, among hominins, forms of bipedal locomotion that appear to be different. One example comes from the differences in the feet of Ardipithecus ramidus (dating back around 4.5 million years) and Australopithecus afarensis (one million years more recent), the latter species showing more advanced adaptations to bipedalism.

What are the implications for the real world?

Human evolution is something that interests and excites a part of humanity today. Therefore, gaining a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that explain who we are and where we come from is part of the construction of our identity. Human evolution matters, and as it is a field where gaps predominate over certainties, it continues to develop a very human characteristic: curiosity.

José Miguel Carretero - pelvis EN

José-Miguel Carretero Díaz

Professor of Palaeontology and Director of the Human Evolution Laboratory at the University of Burgos

For me, as a palaeontologist, it is very interesting that one of the first changes to occur in our evolutionary lineage, as the authors explain at the end of their discussion, was precisely the more lateral (parasagittal) reorientation and shorter length of the iliac bone. Chimpanzees are facultative bipeds, but not very efficient ones (they expend a lot of energy and cannot travel long distances). Small changes in the shape of the ilium simply allowed Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 million years ago), proposed as one of our earliest ancestors, to stand upright somewhat more efficiently than chimpanzees, which could have been a major evolutionary advantage in terms of energy savings and freeing up the arms to, for example, carry more food and travel further.

Continuing with what was said in the press release, I find it interesting to know how these crucial modifications from an evolutionary point of view appear simply by modifying growth or development patterns — lengthening or shortening times or modifying ossification patterns at the cellular level — without the need for enormous mutations or drastic genetic changes. This type of process explains how, without major genetic revolutions, small changes can occur that gradually accumulate and can produce very significant evolutionary results over time.

The effective, efficient and obligatory bipedalism that characterises us is more than just a modification of the ilium, but the authors propose a scenario of gradual changes in three phases in which the new features become established. In short, Darwin would be delighted with this type of discovery, both at the fossil record level, for example, that of Ardipithecus, and those reflected in this work at the molecular level.

Gayani Senevirathne et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People