Potentially fertilisable human eggs generated from skin cells

An international team has succeeded in generating fertilisable human eggs from skin cells using a novel technique. According to the authors, the study offers a way to address infertility, although they acknowledge that further research is needed to ensure efficacy and safety before future clinical applications. Of the 82 functional oocytes generated and fertilised, only 9% developed to day 6, when the experiment ended. In addition, the embryos had chromosomal abnormalities. The results are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Rocío Nuñez Calonge - ovocitos piel EN

Rocío Núñez Calonge

Scientific Director of the UR International Group and Coordinator of the Ethics Group of the Spanish Fertility Society

According to research published in Nature Communications, human skin cells can be used to produce viable eggs. This pilot study demonstrates that cell reprogramming could be a possible way to treat infertility in humans, although further research is needed to ensure its efficacy and safety before clinical application.

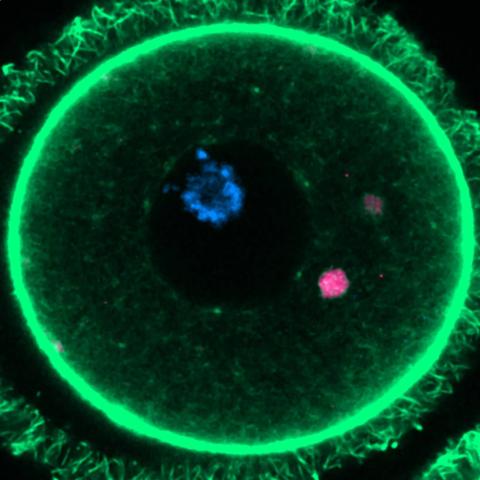

One of the most common causes of infertility is low ovarian reserve with no egg production or poor egg quality, mainly due to the woman's increasing age. In these cases, assisted reproduction techniques are ineffective. Therefore, some researchers have proposed somatic cell nuclear transfer as an alternative. This process involves transplanting the nucleus of a somatic cell from the patient (such as a skin cell) into a donated egg from which the nucleus has been removed. However, while gametes (eggs and sperm) have half the set of chromosomes (23), somatic cells have 46 chromosomes, which would mean that when the egg is fertilised with the somatic cell nucleus, it would have an extra set of chromosomes.

A method has been developed to remove this extra set of chromosomes, which has been tested in mouse models, but its effectiveness has not yet been demonstrated with human cells.

In addition, another added problem is the reprogramming of somatic cells, which are specialised to perform a specific function in the organ from which they were obtained, in order to return to their point of origin, from which they can be transformed into functional cells of any organ in the human body.

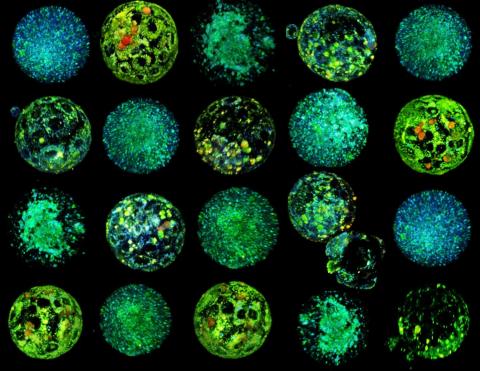

Shoukhrat Mitapilov and his team extracted the nucleus from skin cells and inserted it into donated eggs with the nucleus removed. To solve the problem of the extra set of chromosomes, they induced a process called ‘mitomeiosis,’ which mimics natural cell division and removes one set of chromosomes, resulting in a functional gamete. The process yielded 82 functional eggs, which were fertilised in the laboratory. A small proportion of these fertilised eggs (approximately 9%) developed to the blastocyst stage at 6 days, although all embryos were genetically abnormal.

This study is of enormous importance, as it demonstrates that this process is potentially viable in human cells, opening the door to future research on this technique.

The authors point out several limitations in their study, such as the fact that most embryos did not survive beyond the fertilisation stage and the presence of chromosomal abnormalities in the blastocysts. In addition, they report the impossibility of distinguishing between developmental arrest due to chromosomal abnormalities and incomplete epigenetic reprogramming of somatic chromosomes. Since all embryos analysed had chromosomal imbalances, it is difficult to separate the effects of aneuploidy from reprogramming defects. The modest blastocyst development rate (8.8%) likely reflects the influence of both factors.

The success of nuclear transfer cloning depends on the elimination of somatic epigenetic programmes and the establishment of totipotency in cloned embryos; therefore, more thorough research is required to clarify possible reprogramming errors before considering its clinical application.

In addition, the important ethical considerations of the study must be taken into account. In fact, several years ago, the Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine published a document presenting several ethical arguments against the use of somatic cell nuclear transfer for the treatment of infertility due to concerns about its safety, possible unknown effects on children, families and society, and the existence of other ethically acceptable methods of assisted reproduction.

Cabello - Óvulos piel (EN)

Yolanda Cabello

Independent clinical embryologist and consultant in assisted reproduction and lecturer on the Master's Degree in Health and Clinical Management at the International University of Valencia

The article is a high-quality study that explores, for the first time in humans, the possibility of generating functional eggs from somatic cells—any cell other than reproductive cells (such as eggs or sperm)—using nuclear transfer and an experimental technique. The research is well conducted, with ethical protocols and advanced genetic and cellular analysis techniques.

Reproductive cells contain half of the normal chromosomes of the species, so when they unite, they would form a cell, called a zygote, which would have the normal chromosome set of a human cell. The main novelty is that they were able to induce reductive chromosome division in reconstructed eggs, demonstrating that it is possible to approximate the production of functional human gametes from cells such as skin. This advance represents a potential paradigm shift in infertility treatment, especially in cases where viable gametes are unavailable. Although the technique still needs to be perfected, it opens new avenues for assisted reproduction and the development of in vitro gametogenesis in humans, which would have profound implications, both scientific and clinical.

The main limitations of the study are that most embryos did not progress beyond fertilization or presented relevant chromosomal alterations as the cells divided, and that it is a proof-of-concept study with embryos not cultured beyond day 6. This implies that clinical safety and efficacy are far from assured, and much more research is required before possible clinical application.

In summary, this is a relevant and pioneering work, but still preliminary. It shows that the path toward creating eggs from human cells is possible, although there are biological and technical challenges to overcome before this technology can effectively help patients with infertility.

The use of this technology to generate functional eggs from human cells raises significant ethical dilemmas, especially due to the implications for reproduction, genetic identity, and cell manipulation.

On the one hand, it could offer hope to people with absolute infertility, allowing them to have genetically related children, which represents a major advance in reproductive medicine. However, questions arise about the moral limits of intervening in human life: the generation of gametes and embryos in the laboratory could face debates about the beginning of life, the status of embryos created exclusively for research, and the risks of possible genetic or epigenetic abnormalities in the future.

The most important social and ethical implications include:

- The risk of genetic manipulation and possible non-therapeutic uses, such as trait selection or biotechnological enhancement.

- The possibility of creating offspring without the natural intervention of both parents, which could disrupt traditional cultural and family concepts.

- The creation of embryos with undetected chromosomal or epigenetic alterations, which poses risks to the future well-being of the baby.

- Possible unequal access, if these techniques become more expensive or are limited only to certain social groups.

Furthermore, the study underscores the need for strict ethical and regulatory oversight, similar to what is happening with cloning, which is currently prohibited in humans. The research has followed informed consent protocols and oversight by independent committees, but they recognize that before possible clinical use, much more exhaustive efficacy and safety evaluations and in-depth ethical reflection on the fate of the embryos, genetic identity, and the risks of manipulation would be necessary.

Ultimately, this is an exciting advance, but it requires an open and responsible dialogue between scientists, regulators, and society to decide how and why this technology should be used in humans.

Nuria Marti Gutierrez et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- In vitro