Efforts are being made to increase biosecurity in light of the possibility of manufacturing dangerous proteins with AI

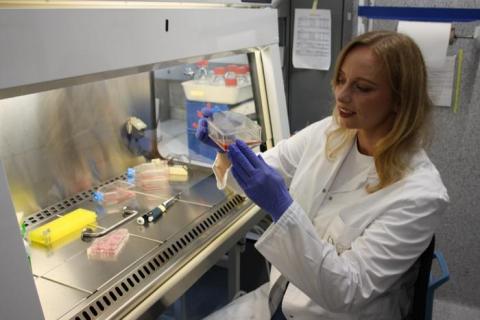

Artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted protein engineering is enabling advances in the design of new molecules, but it also poses biosafety challenges related to the potential production of harmful or dangerous proteins. Some of these threats, whether deliberate or accidental, may not be detected by current control tools. An international team has analyzed the situation and developed software patches to improve their identification, although they acknowledge that it remains incomplete. The authors of the study, published in the journal Science, warn that some of the data and code should not be published in a public repository due to its potential misuse.

Valencia - Software bioseguridad (EN)

Alfonso Valencia

ICREA professor and director of Life Sciences at the Barcelona National Supercomputing Centre (BSC).

Generative AI technologies, as the name suggests, are designed to generate synthetic data. Popular variants like ChatGPT produce artificial texts that are indistinguishable from real texts. In other fields, these same tools are used to create genomes, proteins, medical images, and many other useful scientific and medical applications. The problem, which is evident in the case of ChatGPT, is that in most cases we lack methods to assess the quality of this synthetic data. Can we trust the texts generated by ChatGPT?

This limitation is intrinsic to the technology and may well be insoluble within the framework of this type of approach. So, what can we do? A practical solution, already implemented in systems like ChatGPT, is to use large amounts of data (prompts) that are as comprehensive as possible to test their capacity and consistency, known as "Red Teaming." For example, a system specialized in finance can be asked to answer questions about travel. If they answer, we know they are operating outside their scope and must be corrected. The same is true for avoiding sex- and gender-biased responses, by subjecting systems to systemic questions with their syntactic and semantic variants to assess how often they continue to give unacceptable answers.

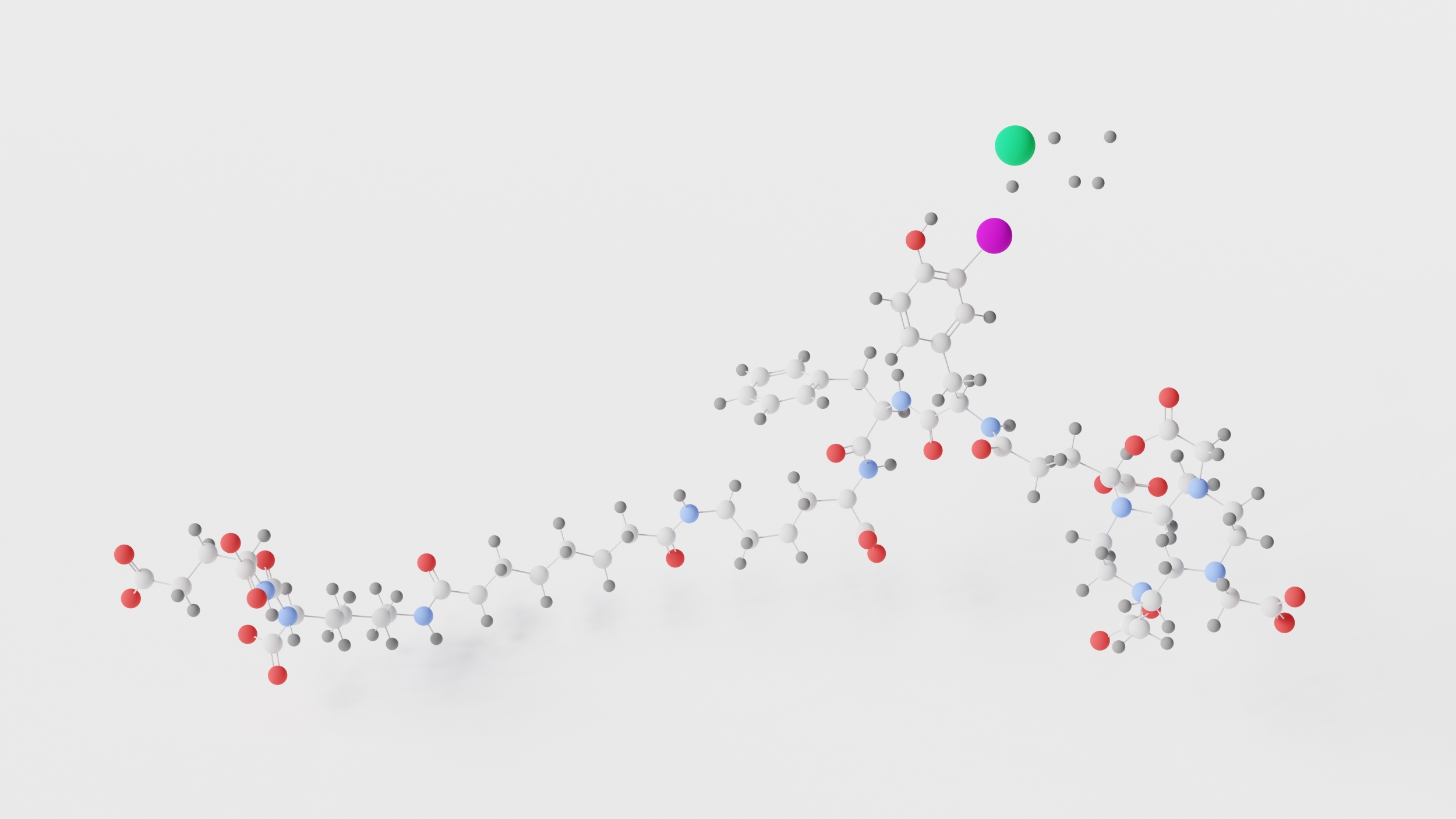

The recent publication applies this same logic to the field of potentially dangerous proteins. The ability of generative AI (GenAI) systems to generate entirely new proteins, with sequences and functions distinct from natural ones, has revolutionized biotechnology and its applications, including biomedical ones—such as the design of new antibodies. In fact, the Nobel Prize awarded to David Baker in 2024 recognized the advances made with these tools in protein design. This is a very positive advance, but it carries a risk: the possibility of generating dangerous proteins. The first thing that comes to mind is a more infectious variant of the coronavirus. A year ago, David Baker himself, along with George Church, a renowned biotechnologist, warned of the dangers associated with protein design using GenAI tools.

Currently, this risk is managed through biosafety screening software (BSS), which predicts the danger of new proteins when their generation (the synthesis of the DNA needed to produce them) is requested. The article demonstrates, first, that when faced with numerous new variants (Red Teaming, equivalent to asking a financial system about travel), the four most commonly used programs fail, and they do so more frequently the further the sequences are from natural ones. Given these results, the authors propose a series of software improvements that, although effective in the cases tested, do not completely or generally solve the problem.

An interesting aspect of this publication is that, according to the journal, the authors have not made their software publicly available to prevent others from developing countermeasures and circumventing the restrictions. This is further evidence of the weakness of these types of approaches and the enormous difficulty in controlling the properties of synthetic data produced by GenAI methods.

Wittmann et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed