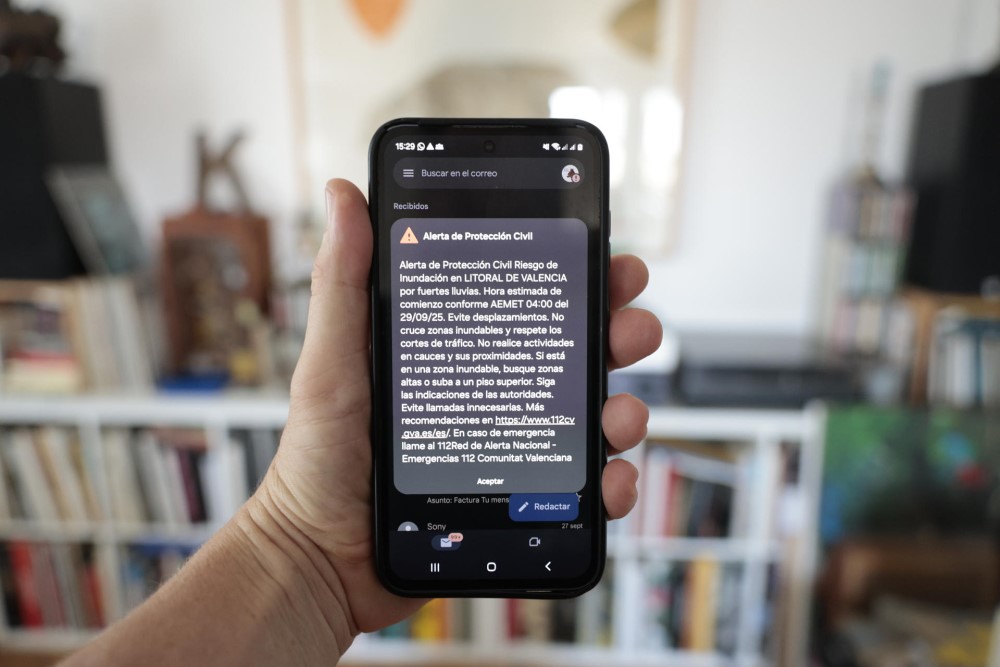

In October 2024, devastating floods affected the Valencian Community and part of Castilla-La Mancha, in eastern Spain, causing more than 200 deaths, damaging around 4.000 homes and buildings, and causing incalculable losses. This extreme weather phenomenon, known locally as DANA (Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos, or isolated high-level depression), concentrated intense rainfall in a relatively small area in a very short period of time.

The Valencia floods are just one example among many around the world. Nearly 2 billion people are exposed to the risk of flooding, according to World Bank data. Climate change, uncontrolled urbanisation, and lack of urban planning increase the frequency and severity of these events.

Floods can leave people homeless, displace entire communities, generate new diseases or worsen existing ones, cause deaths, and have devastating economic impacts, among many other consequences. Those living in poverty often suffer the worst consequences.

Beyond the natural phenomenon and its social and political complexities, one of the clearest lessons from the DANA in Valencia was that the information available did not always meet people’s real needs.

What is reported does not always match what people want to know

During the DANA crisis, the media focused mainly on meteorological data and official alerts. They discussed wind speeds, precipitation, temperatures, and explanations of what a DANA is.

Politicians who participated in live broadcasts during the emergency shared their concerns and feelings, and described the overall situation in their localities.

Very general recommendations were given, such as “use common sense,” “be very cautious,” “avoid unnecessary travel,” “seek higher ground,” and “don't let your guard down, even if it's not raining.”

However, these messages did not always respond to what people wanted to know: how to act, where to take shelter, how to follow up with emergency services, or what to do in specific scenarios.

Today we know that neither colour-coded alerts nor a solid action plan are enough to ensure people know what to do and stay safe. If we want to help the public protect themselves during an emergency, it is also essential to consider how we will communicate the risks and how the information will be received.

At Risk know-how, we analyzed radio and television coverage and compiled nearly 30 testimonials from people who experienced the emergency, including individual interviews and statements in traditional media and on social media. What we found allowed us to identify patterns in what people really wanted to know during the crisis, and how risk communication can be improved to reduce harm in future emergencies.

Here are eight ways to communicate better during flood emergencies.

1. Communicate through the channels people already trust and use

One of the key challenges during a flood emergency is ensuring that information reaches people and keeps pace with how quickly things change.

Information needs to be present in the channels people already use and trust. A single communication channel is not enough for a flood alert and all of the relevant information. Think radio, TV, social media, even loudspeakers in public spaces like the underground.

When possible, work directly with community leaders, as they know the community best and will help spread the message.

Many people said they had no idea an alert had been issued or only became aware of it when they were already in the midst of the emergency.

“I didn’t know anything about the DANA [emergency] until I saw it through the window.”

— Resident of Valencia

“In Paiporta, only ten litres per square metre had fallen – that’s nothing – and no type of alert had been sent.”

— Resident of Paiporta

2. Go beyond warning colours and explain the potential consequences they represent

The risk isn’t the rain – it’s what might happen to people. Using yellow, orange, and red alerts is not enough to convey the potential consequences. It is better to describe how those alert levels translate into real-world impacts—for example, the expected water depth and strength, and what that means in terms of blocked streets, damage to cars and homes, injuries, and deaths.

Many people didn’t realise the risk included being trapped or losing their lives.

[…] "This time it cost many their lives, no one warned them that it wouldn’t be like the other times."

— @Solterav2 on X. 1 November 2024

3. Be as precise as possible about when and where flooding is expected

A clear alert starts with clearly stating the date, time, and area expected to be affected. Always clarify that these estimates may shift as the event develops and stress the importance of keeping up with updated information.

Messages such as “a red alert has been issued for all communities near this river” left people confused about whether their own community was included or not. In addition, many people were unclear about when the flooding would arrive.

“People didn’t go to save the car because they thought it was more important than their life. It’s because they thought they had time. It’s because they weren’t warned when they should have been.”

— @pilar___af on X. 3:38 PM · 31 October 2024

4. Specify who might be affected

The more specific you can be about who is at risk, the more useful the message will be.

For example, people living in specific areas or types of housing, or people of certain age groups, genders, or occupations.

Use clear phrasing like:

“If you live on the ground floor...”

“If your home is near a riverbed...”

“If someone in your household has reduced mobility...” etc.

This way, people can recognise when the message is intended for them.

“We were worried about my friend’s 92-year-old grandmother who lives on the ground floor. The water came in with such force, it destroyed the walls and she had to be rescued with bedsheets.”

— Laura, Paiporta. Live on Hora25, 29 Oct 2024

5. Correct common misconceptions about flooding

Many people believe that flooding only happens after heavy rain in areas with intense precipitation. Alerts should explain that flooding can occur in places where it hasn’t rained at all – water can travel quickly from higher areas and flood lower regions. Clarifying this can help people prepare even when they “don’t see it coming”.

Another common misconception is that cleaning out a riverbed eliminates the risk of overflow. It’s crucial not to overstate the protection such measures provide.

"It wasn’t raining, just very windy – and the streets started flooding as if a tsunami had hit."

— Rocío, resident of Catarroja

6. Give practical advice that takes into account how people in the area have behaved in similar situations in the past

In an emergency, people must make quick decisions in real-life contexts: Can I get the car out of the garage? Should I send the children to school? Should I seek shelter with neighbours? Do I need to move livestock to higher ground?

It’s important to identify possible scenarios, anticipate the choices people might face or how they might act given past experiences, and offer tailored recommendations for each one.

For example, in the Valencia region in the past, people have been advised to go take out their cars from underground garages, so it could be anticipated that they would do that again. In such cases, it is essential to clearly indicate that cars should NOT be removed from garages, even if this was the recommendation in the past.

During the DANA flood emergency, advice was very general – “use common sense”, “don’t take risks”, “avoid the river”, “head to higher ground”. But there was a lack of practical guidance for specific contexts: whether to climb to rooftops, retrieve cars, move to upper floors, stay put or evacuate. Many had to act on instinct rather than clear instructions.

“Unaware of what was coming, I did exactly what you shouldn’t do: I went down to the garage to move the car. I was the last to get it out. I parked it on the pavement and the water was already up to my knees, pouring into the garage like a waterfall.”

— @RiddleZone on X. 11:24 AM · 1 November 2024

7. Remind people that uncertainty is part of flood emergencies and explain where and when to get updates

That’s why it’s essential to keep the public informed on various aspects: the behaviour of the flood, progress of evacuations and rescues, distribution of aid, safety measures, and government/emergency service actions.

To manage uncertainty, it is recommended to communicate:

- what is known

- what is still unknown

- what the advice is in the meantime

- and that advice may change.

Also, tell people where and how often the information will be updated, so they know where to turn.

During the DANA flood emergency, many people said they felt lost, helpless, and abandoned by the authorities and emergency services.

"No emergency number answers – not the fire brigade, not by phone, not even on Instagram."

— Mireya, live on Hora 25, 29 October 2024

8. After the event, follow up

Flood risk communication shouldn’t end with the emergency. A long-term perspective is needed. People have questions: Could this happen again? What’s being done to repair the damage? What long-term solutions are being put in place to prevent future tragedies?

People voiced concern about a lack of information on recovery plans – and feared being forgotten.

"Influencers were coming here on scooters or bikes livestreaming what it looked like. We’re a media circus now, but in a few weeks no one will remember us."

— @RiddleZone, on X. 11:24 AM · 1 November 2024

Being safe requires understanding the risks. Keep these points in mind the next time you need to communicate or respond to a risk during a crisis. They are also summarised in a video.

—A risk communication guide for journalists, also published by SMC Spain.

—The Risk know-how framework, which brings together 20 key concepts about risk, with definitions, examples, and resources.

—A library of resources with materials on risks from around the world and across multiple sectors.

—A workbook that guides you in putting better risk communication into practice in your community.

This article has been reviewed by Leonor Sierra.